1519: The Gospel Breakthrough and the Leipzig Debate

by Mathew Block

It was, perhaps, the year 1519 that was most important to the ultimate direction of the Reformation—for it was only in this year that Martin Luther truly came to understand the good news of the Gospel, according to his own reckoning.

Luther writes that early in this year he was struggling over the idea of the “righteousness of God” as spelled out in St. Paul’s epistle to the Romans. At this point, Luther understood the term to mean the righteousness “with which God is righteous and punishes the unrighteous sinner.” The “righteousness of God,” then, was the threat of God’s wrath. For Luther, the Gospel itself was sorrow, because he believed it promised only punishment for the unrighteous. And Luther was far too aware of his own sin to find joy in such “good news.”

For this reason, in both the 95 Theses and the Heidelberg Disputation, Luther had counselled an attitude of total self-abasement—“self-hatred” and “humility and fear” are his own words—as necessary to “merit” God’s mercy. If we can’t be sinless, he suggests, then we must learn to view ourselves the same way God views sin—with loathing. But in trying to invoke such self-hatred, Luther inevitably found himself angry at God. “I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners,” he writes.

And yet, as he struggled day and night to understand the words of St. Paul in the book of Romans, God at last opened his eyes. “In the Gospel the righteousness of God is revealed,” he read, “a righteousness that is by faith from first to last, just as it is written: ‘The righteous will live by faith’” (Romans 1:17). And suddenly he began to understand that the “righteousness of God” here is not the justice by which He condemns sinners but instead “the passive righteousness with which merciful God justifies us by faith.”

“All at once I felt that I had been born again and entered into paradise itself through open gates,” he writes. The righteousness of God wasn’t condemnation; it was mercy for sinners bought through the death and resurrection of Christ. Luther had long understood the Law; now he understood the Gospel.

“There a totally other face of the entire Scripture showed itself to me,” he writes. As he ran through the Scriptures anew, he saw again and again that it was true: the Gospel was something given to sinful humankind as a gift, undeserved and unearned. It was grace alone, received by faith alone. It was love.

As he ran through the Scriptures anew, he saw again and again that it was true: the Gospel was something given to sinful humankind as a gift, undeserved and unearned. It was grace alone, received by faith alone. It was love.

Even as Luther was finding new peace through knowledge of the Gospel, external events were leading to an ever deeper confrontation with Rome. Andreas Karlstadt, Luther’s colleague at the University of Wittenberg, had challenged one of Luther’s critics, Johann Eck, to a public debate, and Luther had likewise been drawn in.

Throughout July 1519, Luther would participate in this debate in Leipzig, drawing the lines between the Wittenberg party and the Roman church ever more clearly. He strengthened his rejection of the sale of indulgences and disputed the existence of purgatory. But more than any of this, he questioned the authority of the Pope, explicitly stating that neither Pope nor Councils could invent articles of faith if they were not first found in Scripture. It was Scripture alone, he argued, that had authority over the faith.

In one year, Luther had stumbled across the major tenets of the Reformation: grace alone, faith alone, and Scripture alone. These threads would continue to weave their way through the decades and difficulties yet to come.

———————

Mathew Block is editor of The Canadian Lutheran magazine and communications manager of the International Lutheran Council.

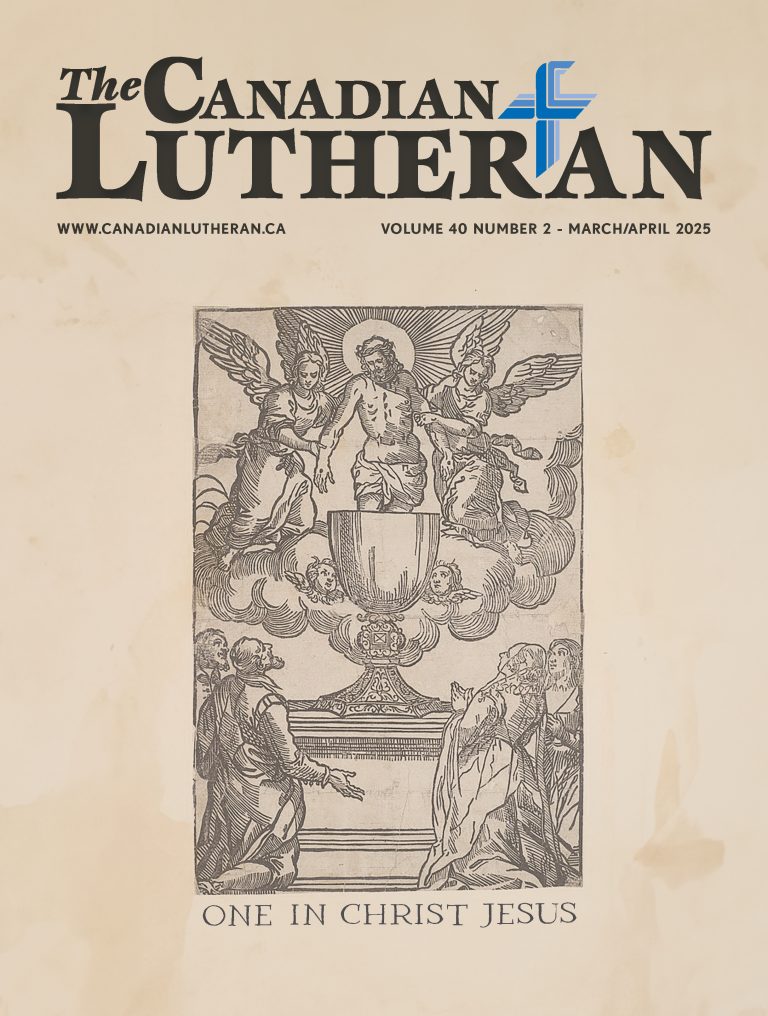

Banner image: Luther discovers the doctrine of justification by faith. “Dawn: Luther at Erfurt.” Joseph Noel Paton, 1861. Qutations from Luther’s Works, Vol. 54.