Paul at the Areopagus: A Model for Apologetics

The Predication of Saint Paul: Joseph-Benoît Suvée, c. 1779.

by Adam Chandler

The word “apologetics” is becoming more common, so some Christians may ask: “What is apologetics anyway?” The simple answer is that it’s a way of defending the faith.

St. Peter explains in greater detail: “In your hearts honour Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect” (1 Peter 3:15). Christ has come into our hearts to deliver us from sin, death, and the power of the devil. In him we have the hope of life eternal.

In this world, we often come into contact with people who do not have faith in Christ. They might be members of other religions, or they might have no religion at all. They have no hope, or rather false hope coming from a false idol. So, as our Lord commanded (Matthew 28:19-20), we wish for them to become fellow disciples of Christ—to receive the same hope of life eternal that we have. Through the gospel message, the Holy Spirit works faith so that an unbeliever may be given the hope of Christ. Apologetics is a way to share the love of Christ as we help people re-examine their beliefs.

Some people have spent their whole lives without Christ. Others have found reasons to reject the Christian hope they once believed. Both kinds of unbelievers have constructed a worldview without Christ, and they may not understand why they need Christ in their world. Assertive Christians might be tempted to “destroy arguments and every lofty opinion against the knowledge of God and take every thought captive to obey Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:4-5), but this can cause more harm than good if they proceed without gentleness and respect. Some Christians may have so much fun storming the stronghold to take it captive for Christ, they do not see the damage they are causing in the process. If we merely argue, rather than show the love of Christ, it can cause offense and raise new barriers.

St. Paul, in his apologetic approach, made himself a servant of all. He became all things to all people so that he might save some (1 Corinthians 9:19-23). Paul never forsook his freedom in Christ, nor did he adopt pagan practices. He simply went to those who did not know Christ, engaged in their lives, and showed them how Christ could bless their lives—how His death and resurrection brings them forgiveness from sin unto eternal life.

The Areopagus Approach

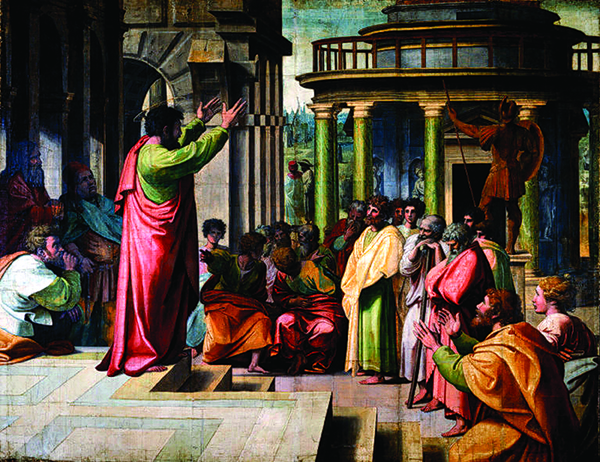

St. Paul preaching at the Areopagus: Raphael, 1515.

Paul demonstrated his apologetic approach when he came to the city of Athens (Acts 17:16-34). He did not go straight to the idol-worshippers of the city to convince them of Christ. Instead, he sought to talk with the Jews first, perhaps asking them about Athenian beliefs. The apostle likely talked with his countrymen in the synagogue who knew the area and its homegrown inhabitants. In the marketplace, Paul spoke with many people, including Epicurean and Stoic philosophers who were well-educated members of the Athenian community. He spoke with philosophers as well as the layman on the street.

Paul took the time to gather information from the locals about their common beliefs before interacting with them apologetically. He learned from the people themselves what they believed in a careful, thought-out process. That’s a valuable approach. It’s certainly helpful for you to visit with your pastor and other Christians to learn more about what non-Christians believe, but it is also good to speak directly to non-Christians about their faith, or to read books and articles to be informed about what others believe.

The key is listening first. Because there are so many kinds of non-Christian beliefs, it is hardly a thoughtful or respectful practice to lump all unbelievers together into one group. A Muslim will not believe the same things an atheist will, nor will either of them agree with a Buddhist—each one must be treated differently to respect their beliefs, but always trusting that the Holy Spirit will work the hope of Christ through our apologetic witness.

Paul went to two major groups of thinkers in Athens: Epicureans and Stoics. The Epicureans were essentially atheists who held that nature operated on its own without any help from the gods (whether gods did or did not exist, they did not care). Epicureans taught that people should be devoted to the pleasures of life (though not in an overindulgent manner) as well as to rational thought. This idea has parallels to the atheistic devotion to science in modern society, as well as to those who spend life in the pursuit of pleasure.

Without God to ground all things, modern atheists tend to focus on material science and logic as the be all and end all. Others eat, drink, and enjoy the pleasures of life “for tomorrow they die”; they do not have the hope of the resurrection (1 Corinthians 15:32).

On the other hand, the Stoics did believe in a god, but this god was the sum total of all things. The universe was god. This means that all things were aspects of god and made from god. A similar idea is present in some Eastern religions today. Paul going to speak to the Epicureans and the Stoics is somewhat like you speaking with an atheist physics professor and a Buddhist monk in order to learn more about what they believe.

Apologetics is sharing the hope of Christ within you and connecting this hope to the listeners’ lives. If they have constructed a worldview upon which they have placed all their personal hopes, dreams, and experiences, then their worldview must be addressed with gentleness and respect. If their beliefs are rejected outright, they may feel like we are rejecting them as people. But the love of Christ does not reject anyone. Instead, it comes to all people, inviting them to be reborn as children of God.

Once Paul had learned all he could about local beliefs in Athens, he stepped out into the Areopagus to speak to the Athenians. The Areopagus was a flat place midway up to the Parthenon, so people would regularly have to pass by on their way to and from the temple.

Paul’s move to engage people there would be something similar to walking onto public access television to deliver a speech. He had spent quite some time with idol worshippers, yet his first words praised the people for being very religious. He did not immediately condemn them for having a false religion; he commended the Athenians for honestly searching for a deity. They had set up an altar to the unknown god. The Athenians were honestly trying to search for the truth, but they did not know that Jesus is the way, the truth, and the life. Whoever sees Jesus sees God the Father (John 14:6-11). The message which Paul delivered demonstrated the love Christ had for the Athenians, because the message was given in gentleness and respect.

Many people today try to find truth through popular science, logic, or meditation. They get bogged down in idols—their own ideas, or self-absorption, or life’s pleasures. How can they believe in Jesus Christ if they have not heard him preached? Jesus cannot be found scientifically or by personal action alone. Jesus is revealed to us by the Word of God. The Athenians of Paul’s day fell into idol-worship because they had not heard God’s Word preached to them. They needed Christ, but did not know they needed Him. Paul praised the people for keeping an ear open for the unknown God and preached the divinity of Christ to them so they might believe.

Paul recognized their search for God had borne fruit in the culture of the Athenians, citing their poets approvingly. He quotes: “in [God] we live and move and have our being” and “for we are indeed [God’s] offspring.” These are the words of two Athenian poets: Epimenides of Crete, and Aratus. Although these poets were not Christian, Paul recognizes the truth of some things they wrote and showed how the Christian God fulfills this truth.

In a similar way, there is common ground between Christians and atheists when the atheist observes that the universe had a beginning. Christians of course claim the universe was created by God while the atheist claims a materialistic cause. While we do not accept a non-Christian explanation of the universe, we do well to acknowledge that we agree with a portion of their viewpoint. It is because the Greeks agreed that we are the children of God and we depend on Him, that Paul could argue against idols and for the resurrection of Christ.

Apologetics bases itself on things that both Christians and non-Christians know. This gives a foundation for presenting the message of Jesus Christ.

Apologetics bases itself on things that both Christians and non-Christians know. This gives a foundation for presenting the message of Jesus Christ. For example, we can say we agree that the universe had a beginning, and the Bible teaches that this beginning was caused by God through the Word. This Word, we may continue, was made flesh and dwelt among us to die on the cross for the forgiveness of sins.

From Theory to Practice

Paul’s encounters at the Areopagus model for us a healthy way of doing apologetics. First, we must know what we are talking about. This does not only mean that we need to know the hope of Christ within us in order to share this hope; we should know what people outside the faith believe. If you find you lack knowledge or understanding about something, ask about it.

Secondly, we should ask people about their beliefs and listen deeply. People will feel respected if you value their personal opinion and try to accurately understand what they believe while you listen with respect. Third, we should acknowledge and build upon agreements. God’s power and nature has been evident since the creation of the world (Romans 1:20) so there will likely be some beliefs a non-Christian possesses that agree with Scripture.

Finally, from that common ground, we should respectfully bear witness to Christ through His Word. Paul spoke at the Areopagus in this way. He acknowledged that the Athenians had some knowledge of God, but that the God of the Bible is different from what they taught. Then Paul declared that a day is coming when all people will be judged. Jesus rose from the dead, conquering the sin of the world, so we too may have newness of life.

It is this hope to which Paul witnessed at the Areopagus, a hope which is itself a gift of God’s grace, given to us by the Holy Spirit. All apologetics should emerge from, and end with, the hope of Christ.

———————

Adam Chandler is finishing a year of vicarage in Trinity (Winkler) and Zion (Morden) Lutheran Churches in Manitoba, and preparing to return for his final year of studies at Concordia Lutheran Seminary (Edmonton).