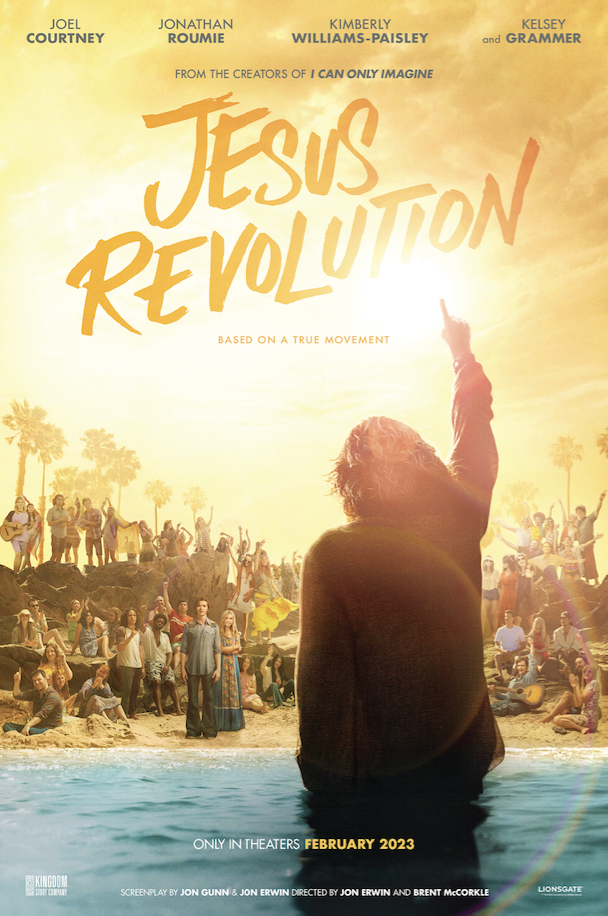

Jesus Revolution: Church history, 20th century-style

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

When Janette Smith brings home a hippy hitchhiker named Lonnie Frisbee to meet her father, Pastor Chuck Smith of Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa, California, Smith is surprised to discover the young man is a street preacher. By embracing the growing swell of hippies being evangelized in the shadow of 1967’s drug, sex, and rock-n-roll “Summer of Love,” Calvary Chapel balloons from a handful of members to a couple thousand regular attendees—a symbol of the era’s “Jesus Movement” and its “Jesus People.”

Directors Jon Erwin and Brent McCorkle’s adaptation of Greg Laurie’s 2018 book Jesus Revolution tells the story of these beginnings and Laurie’s involvement during the early years of what would eventually become a loose affiliation of congregations named after that first Calvary Chapel—a group which eventually branch off into “The Vineyard Movement” and other non-denominational churches.

Pastor Smith, portrayed by Kelsey Grammar, is depicted as an uptight “square” who experiences an epiphany and sees how embracing the cultural zeitgeist of the hippy counter-cultural movement will help reach the lost. In reality, Smith had already begun his movement toward a low-church relaxed approach to congregational life after breaking away from Four Square Pentecostalism due to his exasperation with the bureaucracy and competitive tactics of the denomination’s leadership. But the movie’s two-hour run time brings limitations, with narrative and characters streamlined to keep the plot moving. Some of the congregation’s original members, hard pressed to accept the barefooted, unwashed hippies in the pew next to them, are subsequently depicted in a cartoonish one-dimensional manner. Likewise, Smith and his wife Kay’s adjustment to this “new to them” commune style, Acts 4:32–approach to church life would certainly have been a challenge in real life, but the film may not depict the fullness of their experience.

Kelsey Grammer, best known as the bloviating Dr. Frasier Crane on Cheers and Frasier, turns in a solid performance in the film. Here Grammer deftly plays the initially befuddled yet genuinely warm-hearted Pastor Smith who in the end is faced with some hard pastoral decisions regarding both Frisbee and Laurie’s continued involvement with the church.

The parallel story in Jesus Revolution is about military school dropout and book author Greg Laurie’s relationship with his alcoholic single mother, his personal passage into and out of the “turn on, tune in, drop out” drug culture of the late sixties, and his romance with Cathe Martin as they fall in love and become part of the Calvary Chapel congregation. Laurie and Martin’s story, with all the ups and downs of a conventional romantic drama, forms the backbone of Jesus Revolution’s redemption narrative. The couple become emblematic of a generation which the film depicts as spiritually lost yet searching for truth even while struggling with their own shortcomings, addictions, and problems.

Overall, the film transcends the stereotype of the cheaply-made faith-based Christian film. It isn’t as corny or platitudinous as might be expected.

Overall, the film transcends the stereotype of the cheaply-made faith-based Christian film. It isn’t as corny or platitudinous as might be expected. It has a good musical score and strong cinematography. And the acting is for the most part not bad at all. There is a sense that the people in front of and behind the camera cared about what they were making and rose to the occasion to deliver a winsome high-quality adaptation of Laurie’s book. Jesus Revolution is a well-produced and well-made film.

Lutheran viewers will want to be aware of the film’s repeated emphasis on decision theology. We see, it for example, at Laurie’s baptism as he is asked to make a personal decision for Christ. This understanding of faith—which focuses on individuals choosing God rather than on God choosing them—runs contrary to what the Lutheran Church teaches. As Lutherans, we believe what Luther wrote in the Small Catechism: “I believe that I cannot by my own reason or strength believe in Jesus Christ, my Lord, or come to Him; but the Holy Spirit has called me by the Gospel, enlightened me with His gifts, sanctified and kept me in the true faith.” Calvary Chapel, by contrast, has an Arminian view of salvation, and that’s what is faithfully shown throughout the film.

While Jesus Revolution shows how the preaching and teaching of God’s Word impacts its hearers (Romans 10:17), it also has many of the hallmarks of classic “Anabaptist Enthusiasm,” ranging from a Sacramentarian rejection of the real presence in the Lord’s Supper to the idea that we can receive new and personal direct revelation from God apart from the Scriptures. So it is that we see Lonnie Frisbee prophesy that Laurie will one day preach to thousands of people. These sorts of encouragements can produce outcomes of course (Laurie did go on to preach to thousands through Harvest Church ministries), but should we believe the Holy Spirit spoke directly to Laurie through Frisbee? Such an emphasis on direct revelation can easily be misused.

To its credit, the film delves into the precarious nature of Frisbee’s involvement with the church, proving why the Lutheran Confessions teach that “no one should publicly teach in the church, or administer the Sacraments, without a rightly ordered call.” In the type of congregational polity adopted by Calvary Chapel, the buck ultimately stops with the lead pastor; this leadership style was eventually promoted by Calvary Chapel as the “Moses model.” Ultimately, then, it is Pastor Smith then who “issues” this call to men like Lonnie Frisbee and then “rescinds” it. The film shows the wisdom of St. Paul’s advice to Timothy: “If anyone aspires to the office of overseer… he must not be a recent convert, or he may become puffed up with conceit and fall into the condemnation of the devil” (1 Timothy 3:1, 6).

Jesus Revolution emphasizes the part music played in the history of the Calvary Chapel movement. The Maranatha! Music record label and publishing company began as a non-profit ministry of Calvary Chapel in 1971. The question of contemporary worship music remains a sensitive subject in North American Christianity because the adoption of popular musical styles from the late 1960s and 1970s—an era which promoted an excessively worldly lifestyle antithetical with Scripture’s teaching about sober-mindedness (1 Peter 5:8-9) and moderation in all things (Proverbs 25:16, 1 Corinthians 9:25)— caused division and pain within the church-at-large even as it attempted to reach out to the lost. Pitting Christian freedom against the restraint Christians are to exhibit in their life of faith (1 Corinthians 6:12-20) can cause unnecessary conflict within a church. And we must also recognize that all music comes with its own theological presuppositions, and not all of these are compatible with every Christian theological tradition or confession of faith.

Viewers may also notice that the prominent cross first seen at the front of Calvary Chapel’s sanctuary is quickly covered by a stylized dove representing The Holy Spirit, and that the place once reserved for preaching, teaching, and administering the Sacraments fast becomes the stage for a band. This is a reminder that, when it comes to the art and liturgical life of a church, changes in style are neither neutral nor without substance. There is real danger present whenever we break rapidly from established church practice primarily for pragmatic, rather than scriptural, reasons. Something can be popular and successful by human standards and still be open to criticism, just as something can be sincere and still worthy of careful evaluation. Not everything embraced by the culture at any given moment is appropriate in Church and that’s alright.

These matters can be further complicated by the heightened emotional states produced by such worship styles—emotions which can be sometimes confused with the working of the Holy Spirit. A current parallel can be seen in the widespread adoption of Hillsong music, among others. These groups are rooted in a desire to encounter and invoke God’s presence in worship through songs favouring emotionalism over theological accuracy. A film like Jesus Revolution, whether it intends to or not, may encourage embracing these ideas about worship and music for the viewer, implying that this is the way to grow a congregation. As Frisbee says to Smith: “If you want to reach my people you’re going to have to speak to them in a language they understand.” Some firmly believe this sort of music and the other methods employed by Calvary Chapel, and the churches that followed their lead, are the best way to reach the lost.

Christians can happily rejoice that among the young “Turn on, tune in, drop out” generation of the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were thousands of people who did “tune in” to Jesus. At the same time, we can still be concerned for the long-term stability of the “Jesus Movement” and the faith communities that arose from events like those depicted in Jesus Revolution.

Christians can happily rejoice that among the young “Turn on, tune in, drop out” generation of the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were thousands of people who did “tune in” to Jesus. At the same time, we can still be concerned for the long-term stability of the “Jesus Movement” and the faith communities that arose from events like those depicted in Jesus Revolution. Those who don’t share the same understanding of faith presented in this film should see it as a chance to learn something about another tradition within Christianity. It may also prompt a valid desire to dig into the veracity of the story presented in the film and ask: “Is Jesus Revolution as honest about what it portrays concerning the history of this movement as it purports to be?’

For those interested in investigating a similar sort of story of congregational change in a confessional Lutheran context, look into the story of Rev. Gottfried Martens of Trinity Lutheran Church in Berlin. Their story too involves a congregation which exploded in size—but it didn’t require radical iconoclastic changes to the liturgical life of the church nor the adoption of contemporary cultural styles or modern ideological beliefs. Trinity Lutheran’s story of explosive growth began with a handful of people seeking to be baptised who were turned away by the German state church, only to be graciously received, taught, baptised and cared for by Rev. Martens and the people of Trinity Lutheran—an event which has led the congregation welcome hundreds of refugee Iranian and Afghani converts to the Christian faith.

Films like Jesus Revolution work best when they are viewed not as a step-by-step road map to growing a congregation but rather as an account of God’s work in the lives of Christians. As Christ Jesus says, “The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit” (John 3:8). The strength of Erwin and McCorkle’s Jesus Revolution is its gentle and warm depiction of grace towards those in need of mercy—a testament to the work of the Holy Spirit as He grants repentance and faith in Christ in spite of human pride and selfish ambitions.

Films like Jesus Revolution work best when they are viewed not as a step-by-step road map to growing a congregation but rather as an account of God’s work in the lives of Christians. As Christ Jesus says, “The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit” (John 3:8). The strength of Erwin and McCorkle’s Jesus Revolution is its gentle and warm depiction of grace towards those in need of mercy—a testament to the work of the Holy Spirit as He grants repentance and faith in Christ in spite of human pride and selfish ambitions.

———————

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to The Canadian Lutheran, Reporter; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. For more of his television and movie reviews, check out the Lutheran Movie Review Index.