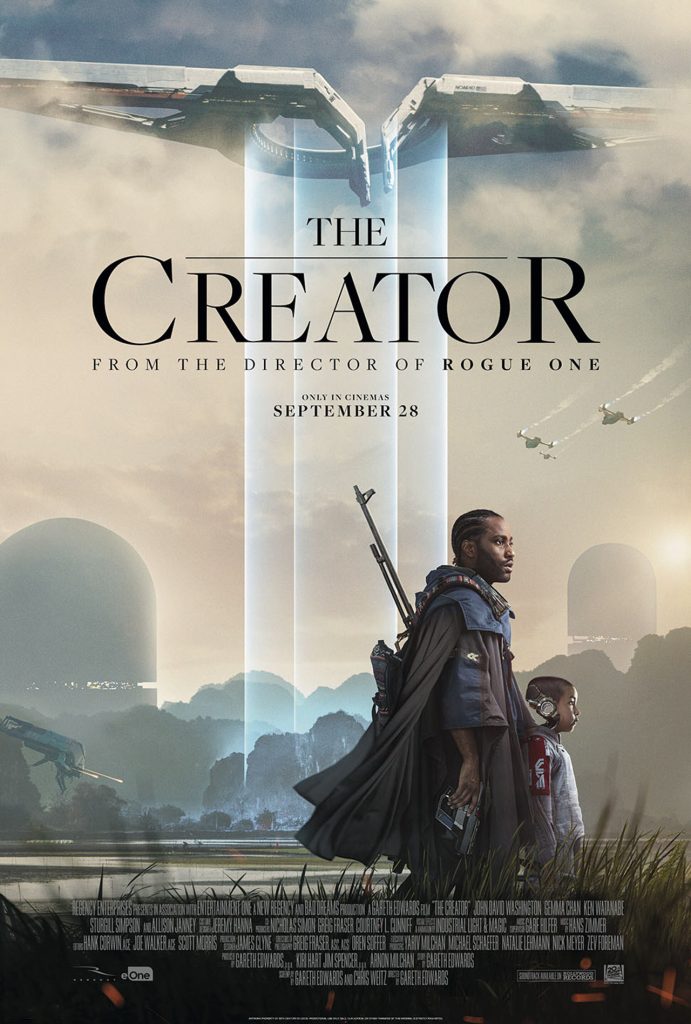

In Review: The Creator

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

In a future where the western world is at war with Artificial Intelligence (AI) while the eastern world seeks to live in harmony with them, growing fears of a secret weapon prompt the American military to attempt to neutralize the AI threat. Roped into the mission is Joshua, an ex-special forces soldier and former undercover operative who ends up on a journey of personal discovery which reveals his own unexpected relationship with the enemy.

One of the central themes in writer/director Gareth Edward’s new film is the intersection between the compassion and love of humanity on the one hand and the synthetic mimicry of AI and advanced robotics on the other. The film asks many interesting questions: Is human love and compassion reserved for what is real? Can AI creations display real emotions, leading to real relationships? Or is it all just sophisticated programming meant to elicit emotional attachments from humans? When questions like this appeared in earlier films, like Ridley Scott’s 1982 film Blade Runner, these were academic questions. Today, they take on real-world importance as the use of AI continues to expand, from common place use in internet search engines and predictive text on mobile phones to more advanced forms like ChatGPT and interactive AI platforms. Meanwhile, Boston Dynamics continues its research in experimental robotics.

While still “futuristic,” the future presented in The Creator seems both familiar today and, in some ways, imminent. Moviegoers will notice that those expressing concern about the uncritical adoption of AI are painted as the story’s villains; those who let their emotions guide their actions are the story’s heroes. If emotion really does trump biology, then who is to say whether emotional attachments—friendship, familial love, even romance—between humans and AI can’t be legitimate? Who could say that the “artificial” is artificial at all? And then, shouldn’t AI deserve all the rights and freedoms enjoyed by humanity? Any response that instead encourages a tempered or critical response to AI is, to this way of thinking, heartless and cruel.

The central relationship in the film is between Joshua and Alphie, an advanced AI in the form of a child. Alphie is the secret weapon the American military is seeking to eliminate—but Alphie may also help lead Joshua to his wife Maya, whom he’d presumed was dead after a botched military raid that blew his undercover mission to find Nirmata (the creator). Maya was believed to be the daughter of Nirmata, a preeminent Asian AI scientist and engineer. While undercover, Joshua fell in love with Maya and married her. At her presumed death, she was pregnant with his child.

At first Alphie is treated as a means to an end for Joshua—something that might help him to possibly rescue his wife. But as the story progresses, Alphie becomes a kind of surrogate daughter for Joshua. By the end of the film, it is revealed that Maya was Nirmata all along, and that she created Alphie to be a synthetic “twin” to their unborn child—thus making Joshua Alphie’s “father.” The emotional entanglement quickly becomes apparent, and Joshua struggles with whether any of it is real or whether it is only his reaction to programming.

The film becomes a kind of transhumanist apologetic as a result, attempting to defend the validity of the merger of the human with the artificial and technological.

By pushing the parental protective buttons in viewers through the character of Alphie, Edwards attempts to draw out more and more sympathetic feelings toward the synthetic. The film becomes a kind of transhumanist apologetic as a result, attempting to defend the validity of the merger of the human with the artificial and technological. In a key moment, Alphie endearingly asks Joshua what heaven is like and if they could go there. He responds that it’s “a place in the sky,” but that he isn’t going there because it’s only for “good people.” Alphie reasons that they are the same: Joshua can’t go to heaven because he’s not good, and Alphie can’t go because AI isn’t a person. This and other moments are meant to garner sympathy for the plight of the AI.

The name “Alphie” is explained as short for the AI’s codename: “Alpha-O.” Christian audiences will easily see the allusion to Jesus, who says of Himself: “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End” (Revelation 22:13). But the ultimate goal for Alphie—as the AI super weapon—is left somewhat unclear. Is Alphie meant to be the end of humanity and the beginning of an AI age without humans? Or is Alphie supposed to bring an end of warfare and the beginning of a time of peace? Is Alphie supposed to be a Jesus figure—a kind of AI incarnation?

Likely not. If anything, Alphie is more of a Buddha figure. After all, Alphie’s “mother” is named Maya after all, and Maya is the name attributed to the Buddha’s birth mother. The film might be made primarily for a western audience, but the overall spiritual underpinnings are eastern. We even get to see AI Buddhist monks in saffron robes! The aforementioned references to heaven and being a “good person” might sound vaguely religious from a western perspective, but the film’s worldview focuses more on eastern notions of Karma and (digital) reincarnation.

Instead, we place our hope in Christ Jesus, who is the true and only Alpha and Omega.

What might Christian viewers make of The Creator? In the face of the kind of war, suffering, and death presented in Edwards’ film, Christians should remember their hope doesn’t depend on their own individual goodness, nor on the promise of a digital download into a synthetic body, nor on the guidance and example of an AI Buddha. Instead, we place our hope in Christ Jesus, who is the true and only Alpha and Omega. For Christians, Christ “was in the beginning with God. All things were made through Him, and without Him was not any thing made that was made” (John 1:2–3). Neither AI nor anything else can take His place.

The Creator is a well-crafted but flawed film, brimming with creativity. It is clearly a cut above much of what has recently been released in the sci-fi genre. But if audiences sense they are being manipulated into embracing ideas with which they disagree, they can quickly be turned off by a film, regardless of how well it is made or how good the acting is. Ultimately, The Creator presents a story designed to appeal to viewers’ emotions in such a way that that their hearts are softened towards transhumanist ideals and the notion of “human rights” for AI. As a result, the film is—intentionally so or not—deeply anti-Christian.

———————

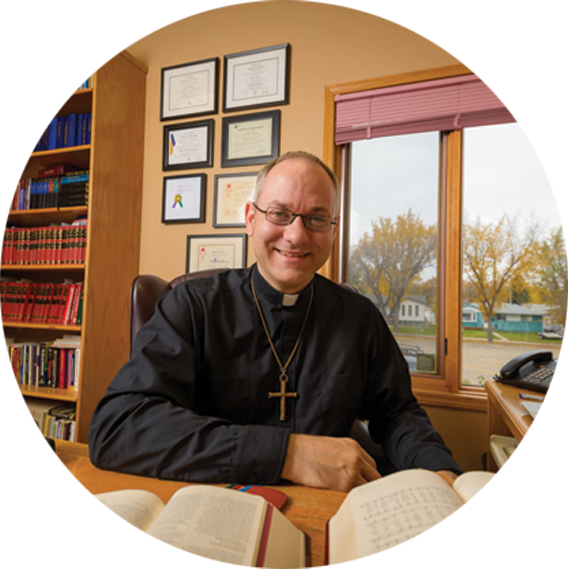

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to The Canadian Lutheran, Reporter; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. For more of his television and movie reviews, check out the Lutheran Movie Review Index.