In Review: Dune: Part Two

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

Focusing on the second half of Frank Herbert’s 1965 science fiction novel, Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two chronicles the rise to power of a young prince thought dead. This occurs after the tragic extermination of his father and people by their sworn enemies, House Harkonnen. The extermination took place shortly after House Atreides arrived to replace them as stewards on Arrakis, the planet that oversees the most lucrative and vital resource in the universe, the spice melange. The spice, found only on this desolate planet where it never rains, facilitates space travel, and extends consciousness and longevity.

At the end of the first film, young Paul Atreides, the rightful heir to his father’s fiefdom, becomes embedded with his pregnant mother, Lady Jessica, among the indigenous Fremen—a semi-nomadic people in the planet’s harsh desert wilderness. Protected by his training in hand-to-hand combat and statecraft, Paul discovers his true protection rests more on a series of Bene Gesserit-crafted prophecies sown on Arrakis over the centuries, intended to appeal to the superstitions of credulous Fremen prone to fanaticism. Paul’s mother uses these prophecies as a weapon to protect her son. Paul knows it’s a pious lie but eventually uses it himself. The key prophesy is of a messianic figure, the “Lisan al Gaib”—the Voice of the Outer World—who will lead the Fremen out of the desert into a green paradise. The presumed death of Paul and his mother is leveraged for surprise as Paul rises to power within the Fremen and seeks revenge on House Harkonnen and their secret benefactor, Padishah Emperor Shaddam Corrino IV.

If the first movie focused on world-building and setting the stage with political intrigue, economics, and ecological concerns, Dune: Part Two shifts gears to focus more on the religious themes of Herbert’s novel. The cynical view of the place of religion in personal and political spheres of life undergirds the 1965 novel, and is likewise apparent in Villeneuve’s films. Contrast this with the 1984 film adaptation which portrayed Paul Atreides as a quasi-divine messiah who could kill with a word and literally make it rain on Arrakis—effectively sidestepping Herbert’s central point that people need to be wary of charismatic leaders and not worship them or treat them like gods. While in both Herbert’s books and in Villeneuve’s films, the character of Paul Atreides is an exceptional, superhuman being called the “Kwisatz Haderach,” produced through centuries of genetic manipulation via a complex Bene Gesserit breeding programme, he is not intended to be understood as divine. Like the prophecies sown on Arrakis, the Kwisatz Haderach is a tool intended by the Bene Gesserit to be used as a mechanism of political and societal control.

Raised as an observant Catholic, Herbert’s view of his religious upbringing is negative, noting his disdain for his Jesuit education…

What can religiously minded viewers make of these themes in Dune? Herbert himself appears to have been agnostic, tending towards atheism. Raised as an observant Catholic, Herbert’s view of his religious upbringing is negative, noting his disdain for his Jesuit education and the influence of his maternal aunts, who, as nuns, forced their religious views on him as a boy (they serve as his key inspiration for the Bene Gesserit sisterhood). Film director Villeneuve was also raised as a Catholic and considers himself a product of the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s in Quebec. While he maintains a fondness for some aspects of his early exposure to Roman Catholicism, his views on the relationship between church and state are thoroughly secular. In a February 2024 interview with The Montreal Gazette, Villeneuve commented that, “as a French-Canadian Catholic living in Quebec under the pressure of the Church,” he was preoccupied with the mix of religion and politics, stating that “the pressure of religion, the idea that you can use God as a tool to manipulate people, is something I think that’s very relevant today in certain parts of the world, including ours.” These themes in Herbert’s books resonated with Villeneuve, making him a good fit to convey Herbert’s thoughts on the dangers of religion used as a tool of control in politics.

The three main Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all have prophetic texts involving messianic figures. Jews still await a Messiah, Muslims await the Mahdi, but Christians recognize the prophesied Messiah as having arrived in the person of Jesus the Christ. Christian viewers should remember that Herbert wrote the character of Paul Atreides as a cautionary figure who is not divine, and so should not consider Paul a Christ figure. While some in Jesus’ day likely desired Jesus to set Himself up as their political leader against outside oppressors (like Paul Atreides), this is not what Jesus did (Matthew 21:1-17; Mark 11:1-11; Luke 19:28-40; John 12:12-19). So too, Paul’s goal of vengeance is very unlike Jesus. Paul’s mother, Lady Jessica, criticizes Paul on this point, saying, “Your father didn’t believe in revenge.” Paul responds “I do”—a sentiment that clearly distinguishes his character from Jesus.

In Dune, Herbert draws a lot on Islamic religion. Muslims consider Jesus a prophet but not divine. They teach that Jesus did not die on the cross but only “swooned” and appeared dead. Christians, on the other hand, consider this teaching heretical and maintain that Jesus died and was resurrected three days later.

The importance of these religious differences becomes relevant in Dune: Part Two. In both the book and film, Paul’s transformation into the Kwisatz Haderach is triggered by consuming “The Water of Life,” a spice rich substance extracted from the bile of young sandworms. Normally, only the exclusively female Bene Gesserit take this water as part of a ritual to become Reverend Mothers; it is considered poisonous to men. When Paul consumes it to induce a metamorphosis, he falls into a deep coma and appears dead. After a Sleeping Beauty-like awakening with the help of Chani’s tears, the fanatical Fremen leader Stilgar sees this as incontrovertible proof that Paul is the Lisan al Gaib—their Messiah. Herbert, and by extension Villeneuve, present this metamorphosis as clever biological manipulation rather than a miracle, reflecting a materialistic view of the universe that dismisses the supernatural out of hand as a superstitious misinterpretation of the natural world. It also reflects the Muslim narrative that Jesus only swooned and didn’t truly die at His crucifixion.

The theme of materialism runs throughout the novel and is also hinted at in Villeneuve’s films. For example, the giant sandworms of Arrakis are worshiped by the Fremen as gods. The Fremen even make knives out of their teeth and incorporate this into their mystery religion. But from a more scientific standpoint, these massive animals, essential for producing the spice and maintaining the desert ecology, are simply biological beings with no supernatural or mystical qualities. Herbert sees mystery and miracles simply as unexplained natural phenomena which can be exploited to enslave the naive.

Herbert and Villeneuve tap into cynical historical critiques of the Messiah figure, challenging the very idea of a chosen one.

Paul initially hesitates to deceive the Fremen, knowing that his spice-induced prescience reveals a future filled with bloodshed if they follow him as their Messiah. But the Fremen view every action or inaction by Paul as a confirmation of his Messiah status. There are parallels (though not comedic) here to the Monty Python film Life of Brian, in which a man born in the stable next door to Jesus spends his life being mistaken for a Messiah. Herbert and Villeneuve tap into cynical historical critiques of the Messiah figure, challenging the very idea of a chosen one.

Christians confess Jesus to be the prophesied Messiah of the Old Testament. Apart from Jesus, though, the Bible counsels Christians to be wary of charismatic leaders who claim divinity or allow themselves to be treated like gods. Jesus Himself warns His disciples that “many will come in My name, saying, ‘I am the Christ,’ and they will lead many astray” (Matthew 24:5). The Psalms likewise teach this bit of wisdom: “Put not your trust in princes, in a son of man, in whom there is no salvation. When his breath departs, he returns to the earth; on that very day his plans perish” (Psalm 146:3–4). The Christian Scriptures, therefore, contain warnings about political leaders and false messiahs—lessons worth considering regardless of one’s religious convictions.

With excellent cinematography, realistic CGI, and an engaging score, Dune: Part 2 is a strong continuation of Villeneuve’s first film. But despite these strengths, the film lacks overall energy, and the pacing is slow, meandering towards an abrupt conclusion—all while some of the most important moments are passed by too quickly.

Those familiar with the book will note some changes in the film when it comes to plot and character. Some of these are positive, like the narratively satisfying confrontation between “The Beast” Rabban Harkonnen and the beleaguered Gurney Halleck. Changes to the character of Chani, meanwhile, are more controversial. In the book she is a true believer, but in the film she is turned into an audience surrogate skeptic. Another change is to the character of Paul’s sister, Alia Atreides. In the book, the character is referred to as an abomination: a small child with the intelligence and mannerisms of an adult (resulting from her exposure to the “water of life” when her mother was pregnant). In the film, though, Villeneuve has condensed the time-frame of the story from a couple of years to about six months. As a result, Lady Jessica is still pregnant. Villeneuve’s solves this narrative dilemma by having Alia communicate as a pre-born telepathic baby (perhaps inadvertently reinforcing the belief that life starts at conception).

Some viewers have compared Villeneuve’s films to Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, lauding them as an example of what contemporary film could be, if it took a more mature storytelling approach and respected source material. Audiences recognize that Villeneuve is trying to value viewers’ minds and is encouraging them to dig deeper into Herbert’s ideas—as opposed to churning out vapid content focused on profiting from established intellectual properties. While Villeneuve’s film may simplify elements of Herbert’s books, audiences will appreciate how Dune: Part Two sets the stage for the recently announced Dune: Part Three, which Villeneuve is also set to direct.

———————

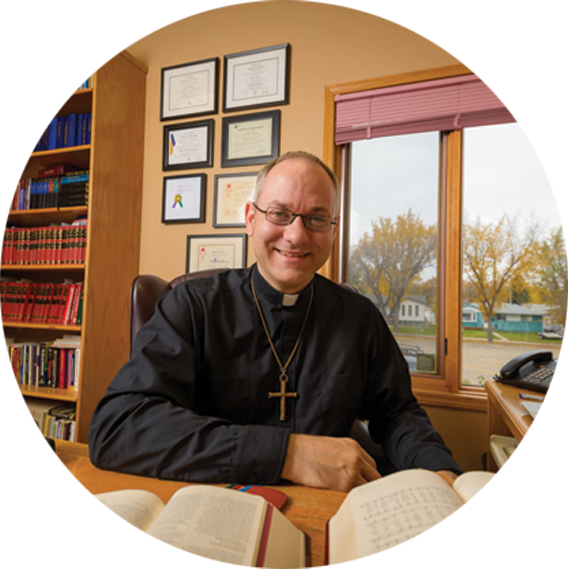

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church in Regina, and movie reviewer for Issues, Etc.