Joker: Folie à Deux: “A Clown with His Pants Falling Down”

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

Imprisoned in Gotham’s dismal Arkham Asylum for the criminally insane, Arthur Fleck awaits trial for multiple counts of murder. There, in a music program in the minimum security wing, Fleck meets Harleen ‘Lee’ Quinzel. The disturbed Fleck and psychotic Quinzel fall into a shared delusional disorder—“folie à deux,—revolving around the iconic persona of the Joker. The primary expression of this shared psychosis is their mutual love for show tunes and popular music. This pushes Joker: Folie à Deux into the genre of a musical, a significant departure from 2019’s Joker.

Not everyone enjoys musicals, which is one reason this film has been so divisive among ardent Joker fans. While Phillips’ initial film struck a chord with its core audience, this new film’s exploration of the Joker character is, disappointingly, not music to their ears. Phillips’ goal here is more character study than fan service. From the opening Looney Tunes-style cartoon, it’s apparent that the film will subvert expectations. Later, during a fantasy sequence reminiscent of the classic Sonny and Cher Show variety television series, Fleck, as the Joker, provides a meta-commentary on the desires of the target audience when he says to Harley Quinn: “I got the sneaking suspicion that we’re not giving the people what they want.”

The Joker, Batman’s arch-rival supervillain, first appeared 84 years ago in 1940 and has since gained a cult-like status among fans, some of whom embrace a shared affinity for the chaos and anarchy embodied in the character. When Phillips’ first Joker film was heading to theatres, concerns arose that it could spark real-world acts of violence—partly because Heath Ledger’s portrayal of the Joker in 2008’s The Dark Knight was linked to the horrific shooting at a screening of the film in Aurora, Colorado. That incident saw 12 people murdered and more than 70 others wounded. Fortunately, the 2019 film did not lead to similar violence—and it’s unlikely the sequel will either. The reason? Phillips is not giving such obsessive fans what they want. Instead, he’s giving them a tale of repentance—or at least that’s the Christian term for it. The film’s pivotal moment finds Fleck sincerely confess before the jury in his court case, “It was all just a fantasy. There is no Joker. It’s just me. I killed six people. I wish I hadn’t. But I did.” This confession breaks the folie à deux between Fleck and Quinzel, who serves as a kind of surrogate for real-world fans who idolizes the Joker. As Quinzel walks out of the courtroom in disgust, so too the real-world fans she represents have metaphorically walked out on Phillips and his portrayal of their beloved unhinged clown.

The opening cartoon sets the tone for the entire film. It features Fleck and his evil shadow vying for control of the Joker character, only for them to become one by the end of the cartoon. This rather on-the-nose hint suggests that the integration of Fleck’s shadow self, as the psychologist Carl Jung would put it, may be the film’s crowning achievement. Jung developed this idea in part through his exploration of the medieval alchemical idea of solve et coagula, meaning to “dissolve and coagulate.” In many ways, the first film saw Fleck formed into the Joker by his narcissistic mother. In this second film, it’s his narcissistic love interest, Quinzel, who wants the Joker to prevail and Fleck to dissolve into nothingness.

Together, these two films transform Phoenix’s portrayal from an origin story of the Joker to a denial of the character.

Together, these two films transform Phoenix’s portrayal from an origin story of the Joker to a denial of the character. This advances the character arc beyond anything seen in previous iterations of the Joker. Taken as a whole, the two films are not about “sympathy for the devil,” but rather the “renunciation of the devil and all his works and all his ways.” In an unexpected twist, Phillips’ two Joker films do not lead to the shedding of Fleck, where only the Joker remains. Nor do they entirely embrace the Jungian concept of integrating the shadow self or the alchemical idea of coagulation. Instead, Phillips delivers a character study where the moral is about setting aside fantasy and taking personal responsibility—even for the worst of actions. Fans hoping to see the origins of a Joker ready go toe-to-toe with Batman will be disappointed.

It is refreshing to see something of a sympathetic portrayal of a villain who, in the end, refuses to play the victim of his past, instead accepting the reality of his crimes. For Christians, after all, such a confession of sins is a prerequisite for forgiveness. Christian viewers are taught to be interested in all people, even villains—perhaps especially villains—reaching a state of repentance and forgiveness. But the film lacks any absolution for Fleck following his confession. Instead, Phillips offers a bleak downbeat conclusion, where Fleck “gets what he f***ing deserves,” dying at the hands of another inmate as a sad punch-line to a twisted joke. The glamour of evil evaporates. Fleck doesn’t get the girl, doesn’t achieve fame—only infamy. Crime doesn’t pay, law and order win, and the fanatics who idolize the Joker are called to reconsider their idolization of the character.

In retrospect, this conclusion shouldn’t be surprising. Many of the musical selections established in the first act of the film contain Christian themes of judgment. The song “Get Happy,” here sung by Quinzel to Fleck, includes the lyrics: “Shout hallelujah, Come on, get happy, Get ready for the Judgment Day.” Even “When The Saints Go Marchin’ In,”—ironically sung by the prison guards and inmates as they march them to empty their bedpans—points to the final judgement. When carefully considered, it also alludes to the hope of being counted among the redeemed in Christ who will enter heaven on The Last Day.

Many of the musical selections established in the first act of the film contain Christian themes of judgment.

On the one hand, all of this sets the stage for a film where Fleck must ultimately face judgment, not just in the eyes of the ardent fans but also in the eyes of God. On the other hand, it raises the question: will Fleck also receive forgiveness? It’s worth noting that Philips musically bookends the tragic character of Fleck with Frank Sinatra’s song “That’s Life,” which includes the futile lyric: “You’re riding high in April, shot down in May.” That implies that there may, in fact, be no hope for Fleck. And the ironic use of the song “That’s Entertainment!” at key moments of the film highlights the sad fact that all of Quinzel’s interactions with Fleck amount to nothing but self-serving lies designed for her entertainment—further indicting viewers who desire their favourite villain to remain the same and not change for the better.

The film offers another warning: Fleck’s shadow may not be merely his own dark “shadow” self but something more sinister, something even demonic. This becomes apparent when Fleck is stabbed to death. The murderer, framed in the background, is seen using his shiv to carve the Joker’s smile into his own face. This act is punctuated by the continuation of the lyrics from Sinatra’s “That’s Life”: “But I know I’m gonna change that tune, When I’m back on top, back on top in June.” In context, the “I” here may be interpreted as the Joker archetype as opposed to Fleck personally. Thus, while Fleck denies himself and the devil, the spirit of the Joker lives on to tempt others toward chaos, anarchy, and violence in the future. We are left with the impression that this may have been the case with every iteration of the Joker.

When Fleck first sees Quinzel singing in the music program in Arkham’s minimum-security wing, she’s singing the 1907 hymn “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” a song about facing death with Christian faith. In the early stages of the film, the audience is left with the question: Will their shared delusion last or will it be broken? The circle of their relationship is ultimately broken, and by the end of the film so too is the bond between Fleck and the Joker. Though Phillips stops short of having Fleck receive forgiveness and embrace Christian faith, the abundance of Christian-themed music throughout Joker: Folie à Deux provides a film haunted by that possibility.

This film may never find an audience. It will likely be too dark for most fans of musicals and too disappointing for those invested in the established fantasy of the iconic DC Joker character. It may, however, intrigue viewers interested in digging deeper into the character of the Joker, considering him in light of the true nature of evil and the desperate need for redemption faced by all those oppressed and trapped in their sinful condition amidst an ever-broken world.

This film may never find an audience. It will likely be too dark for most fans of musicals and too disappointing for those invested in the established fantasy of the iconic DC Joker character. It may, however, intrigue viewers interested in digging deeper into the character of the Joker, considering him in light of the true nature of evil and the desperate need for redemption faced by all those oppressed and trapped in their sinful condition amidst an ever-broken world.

———————

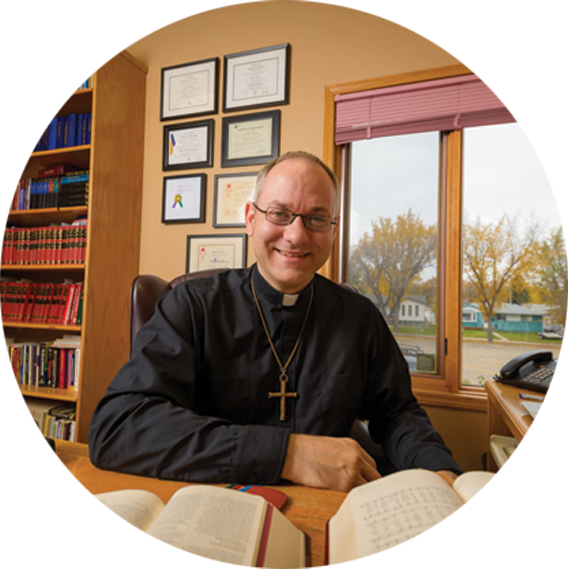

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church in Regina, and movie reviewer for Issues, Etc.