A Reformation unleashed

by John Stephenson

The closing words of President Teuscher’s acceptance speech at last October’s synodical convention caught my attention at the time and have retained it since: “And may the Lord have mercy on our poor little Lutheran Church–Canada!” In the world of public relations, positive “spin” is everything, the magic ingredient that causes people to be self-satisfied and feel good, the factor that can presumably be relied on to make the dollars flow in.

The closing words of President Teuscher’s acceptance speech at last October’s synodical convention caught my attention at the time and have retained it since: “And may the Lord have mercy on our poor little Lutheran Church–Canada!” In the world of public relations, positive “spin” is everything, the magic ingredient that causes people to be self-satisfied and feel good, the factor that can presumably be relied on to make the dollars flow in.

In the setting of divided worldwide Christendom we need to be careful not to get caught up in playing the “numbers game,” an exercise that invariably involves manipulating statistics. Yes, there are way over one billion Roman Catholics on the face of the earth, but how many of them were at Mass last Sunday, and how many of them know and embrace the basics of the Catechism? Since the Soviet Union fell, the numbers of Orthodox Christians have shot up: a huge proportion of Russians are now happy to be associated with their national church and to use it for rites of passage such a being “hatched, matched, and dispatched.” But how much of their gripping Divine Liturgy do they know by heart?

For at least a couple of generations past, Lutherans and Anglicans have jostled for third place among Christendom’s “big players”, but the answer to the question which communion is the larger of the two depends on discerning which side has more artfully cooked the books. The number of Lutherans worldwide can soar to 70 million if we include most of the population of heavily secularized Scandinavia and a good number of church bodies that have not been meaningfully Lutheran for generations, even centuries. And Anglican numbers can rocket towards 80 million if around 27 million baptized Anglicans in England are placed in the balance, notwithstanding the fact that practising members of the Church of England have dipped way below the one million mark. Moreover, to the discomfort of both Anglicans and Lutherans, the Pentecostals are by now likely the third, if not the second largest group of Christians here below.

What did Luther begin?

1527 was in some ways a watershed year for Dr. Martin Luther. Married now for two years and a father for one, by the standards of the day he was closer to old than middle age. From his table talk and some comments in his lectures, we know he was pondering what all he had unwittingly unleashed in the closing months of 1517, some ten years earlier. During 1527 the Reformer wrote a major, brilliant, and powerful defence of the real presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. He also lectured diligently at the university. He and Katie stayed in town during a virulent outbreak of the plague which put their own lives on the line. And in 1527 Luther suffered a terrible breakdown which put him out of commission for a couple of months during which his Anfechtungen (temptations/afflictions) returned in full force.

What then were the heresies that had followed Luther’s brave testimony?

As he began his university lectures on Titus, Luther came out with an unexpected remark: ”Blessed be God that He did not reveal to me [ten years ago] that heresies like these would follow; [had He done so, I would not have begun” (see AE 29:8). The Reformer certainly believed that the Pope and many clergy and teachers of the Church had been teaching a terrible mix of heresies when the Reformation began, and they were manifestly still doing so. What then were the heresies that had followed Luther’s brave testimony? What were the false teachings that had sprung forth as it were from the coat tails of the movement Luther had inaugurated?

Quite against his intention, by refusing to buckle under the pressure exerted by Cardinal Cajetan, Pope Leo X, and Emperor Charles V, Luther unleashed an epoch of pluralism within Christendom, whose full consequences would take more than a century to become plain. He had so to say “let the genie out of the bottle” or “opened Pandora’s Box.” In the aftermath of last year’s Reformation 500, it would be worthwhile to review the slow process by which religious toleration and the coexistence of separated Christian churches became the norm with which we are familiar today. But for now, let’s stick to the topic of Luther’s dismay in 1527.

Cracks began appearing

Pandora’s Box started to let out some weird characters while Luther was holed up in Elector Frederick’s protective custody in the Wartburg Castle for most of 1521. Don’t think for a moment that Pentecostals and Charismatics only showed up within the last century—the three “Zwickau Prophets” won that race when they showed up in Wittenberg and claimed God was talking to them directly, even apart from the Scriptures; infant Baptism was one of the targets in their sights. Given that nature abhors a vacuum, the Wittenberg faculty needed a leader while Luther was away.

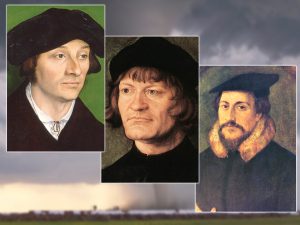

Senior professor Dr. Andreas Karlstadt already thought he could lead the new spiritual movement better than Luther, and he now stepped forth promoting liturgical vandalism and the destruction of religious art. Twentieth-century scholars have described Karlstadt as “the first Baptist,” and he became a major bogeyman for the orthodox Lutherans of the sixteenth century.

When Luther returned without Elector Frederick’s permission from the Wartburg to Wittenberg and preached a sermon series during the first week of Lent 1522 (the so-called Invocavit Sermons, which remain a masterpiece of pastoral theology), he soon grabbed the steering wheel of the Reformation back from Karlstadt’s unsteady hands, but within a couple of years the two former allies engaged in a mighty battle of words. Luther’s powerful treatise in refutation of Karlstadt, Against the Heavenly Prophets, spelled out core doctrine and breathes what from that point on has existed as a “Lutheran ethos.”

Andreas Karlstadt was one of the first to deny that the consecrated bread and wine in Holy Communion are our Lord’s true body and blood. So zany was his line of argument that Luther believed his novel errors would have no traction. But a lawyer in Holland (Cornelius Hoen) had already gently argued for the same position back in 1521. Then Luther was troubled that the Bohemian Brethren, a small church body across the border of Saxony that should have been his natural ally, were hesitant and ambiguous on this central article of faith. But these phenomena were minor in comparison with what burst forth from Switzerland in the mid-1520s as Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich jumped on Karlstadt’s bandwagon and attacked Luther as a major heretic for his confession of the real presence.

Further reforms appear

Zwingli’s attack not only on the Reformer personally but—more importantly—on the Lord Himself in the upper room—triggered Luther’s breakdown of 1527. Even before the warring parties met for their famous Colloquy at Marburg Castle in October 1529, the unity of what would soon be called Protestantism lay smashed to smithereens. Since that time Lutheran Christendom had been caught within a pincer. While Luther lived, the Roman side seemed dispirited and depleted, but from the 1540s onwards the Counter-Reformation was building up a head of steam which remained a powerful spiritual force till the death of Pope Pius XII in 1958. And now we must consider the successors of Karlstadt and Zwingli, who had been the original movers and shakers of Reformed Christendom.

The French theologian John Calvin (1509-1564), who spent much of his career in exile in Geneva did not factor greatly on Luther’s radar, but in the 1550s he emerged as the leading teacher and guide for much of Protestantism. For the next century Calvin, and especially his monumental Institutes of the Christian Religion, were the major force in the spiritual life of the Netherlands, the British Isles, some of France, and—before long—North America. Most troubling from our perspective, not a few German princes who had brought their territories into the sphere of the Lutheran Reformation came to believe that Calvin completed a Reformation Luther had only half implemented, with the result that around the year 1600 a noticeable chunk of Germany had switched from Lutheran to Reformed Christendom.

In 1555 the Reichstag at Augsburg avoided the outbreak of war within the Empire by acknowledging the right of two confessions to coexist within its bounds. Still centuries away from modern concepts of human rights, the Reichstag decreed that the prince of a given territory could opt—with executive effect for all his subjects—between the “old religion” and the Augsburg Confession. To begin with, this arrangement boded well for Lutheranism since three of the Empire’s seven leading princes, the so-called Electors, professed the Augsburg Confession. But by 1600 around ten princes had defected to the Reformed side of the aisle, most prominently the Elector Palatine of the Rhine who finally turned his territory Reformed in 1583. A glance at the map of the confederated Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) will show that in some significant parts of Germany the Reformed have a monopoly of the “Protestant” franchise!

Switching sides

In 1613 the Elector of Brandenburg personally renounced the Lutheran and embraced the Reformed confession. John Sigismund expected his subjects to follow suit and was taken aback when the mass of the nobility, the clergy, and the common people stuck to their Lutheran guns. Initially, the Elector backed off insisting he would not violate the consciences of his Lutheran subjects. But within a few years the House of Hohenzollern (the surname of the rulers of Brandenburg) began a steady war of attrition against Lutheranism within their territories; the saintly clergyman, theologian, and hymn writer Paul Gerhardt was one of the more notable casualties. Tragically, through inheritance, marriage alliances, and a string of aggressive wars, the Hohenzollerns carved out a major state which morphed from Brandenburg-Prussia to the Kingdom of Prussia, the aggressive, militaristic state that bore major responsibility for the 20th Century’s two world wars.

As he spoke candidly and with horror in his lecture room in 1527, Dr. Luther was spared the knowledge that three different Churches would spring on German territory from the movement he had unleashed

Within three centuries, the huge majority of Lutherans in Prussia had caved in to the religious agenda of their royal rulers with only a small minority resisting King Frederick William III’s proclamation of the Prussian Union (of Lutherans and Reformed into one Church) in 1817.

As he spoke candidly and with horror in his lecture room in 1527, Dr. Luther was spared the knowledge that three different Churches would spring forth on German territory from the movement he had unleashed. Some Germans would knowingly embrace Reformed Christianity with its different perception of Christ, the Gospel, and the Sacraments. Many—indeed, numerically by far the largest of the German Protestant churches in the early 20th century—would succumb to Union with the Reformed. Only a shrinking minority would remain meaningfully Lutheran. Faithful Lutherans have been pushed to the margins of the churches now gathered in the “United Evangelical Lutheran Church in Germany” (VELKD), with the result that the strongest Lutheran presence in Germany is supplied today by the heirs of those who resisted the Prussian Union, the “Old Lutherans” who now form the Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church in Germany, our sister—indeed, mother—church, Selbständige Evangelisch-Lutherische Kirche — SELK.

A remnant remains

Statistically, this has been an unhappy tale but statistics aren’t everything. Remarkably, the strongest congregation in the SELK is in the Hohenzollerns’ backyard. At Trinity Church in the suburb of Steglitz, Pastor Gottfried Martens preaches a message and celebrates services that would have landed him in jail two centuries ago. A marvel of this secularist age has occurred as more than a thousand former Muslims have embraced the Small Catechism in faith and practice resulting in the number of faithful Lutherans in Germany inching slightly upwards for the first time in decades.

Christ remains Lord, whatever the rulers of this age may say and do to the contrary.

Rev. Dr. John Stephenson is Professor of Historical Theology at Concordia Lutheran Theological Seminary in St. Catharines, Ontario.