Alien: Covenant—Exploring creation and creators

by Ted Giese

Alien: Covenant is the sequel to 2012’s Prometheus. Both films, directed by Ridley Scott, are prequels of Scott’s original film Alien, an outer space horror film with the catchy tagline, “In space no one can hear you scream.” The premise of the original film and the prequels is the danger found in the void of space—not simply a lack of oxygen, food, and habitable land, but hostile alien life. The whole Alien franchise investigates the fears accompanying the discovery of alien life. Where the original Alien focused more on visceral fear, Prometheus and Alien: Covenant centre on the cerebral fear grounded in the question, “Where do these aliens come from?”

Many of the fears and questions presented in Scott’s Alien films transcend their sci-fi genre and can be found peppered throughout history. The original Alien film could just as easily have been a period piece set in 1849 about prospectors trapped in an isolated corner of the Rocky Mountains accosted by a hungry grizzly bear methodically eating them one by one. Fears associated with exploration or even camping in extremely isolated environments inform Scott’s first Alien film—and what environment is more isolated than space? So, with their lives already hanging in the balance the central struggle facing the 1979 film’s space crew wasn’t, “Where are these aliens from?”, but “How can I keep from dying a horrible death out here in space?”

That primal question eventually becomes the central concern in practically every film in the Alien franchise whether directed by Scott or not. But in the first Alien film the audience is right there along for the ride. After watching the first film, there is a sort-of detached quality to watching the rest of the Alien franchise films because most viewers come with some idea of what’s about to unfold. With Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, Scott takes advantage of this and spends time teasing out the question, “Where do these aliens come from?” Behind that question is an even bigger question for Scott, “Where does anything come from?”—or put another way, “Where does everything come from?” Did it come from nothing? Is there an unchangeable mover? A designer? A creator? God? And then, if there is something behind everything, the follow-up question becomes “What is the nature of creation?” Is it a good thing or not? Is the ability to be creative a good thing or is it dependent on who is doing the creating?

Where does everything come from? Did it come from nothing? Is there an unchangeable mover? A designer? A creator? God?

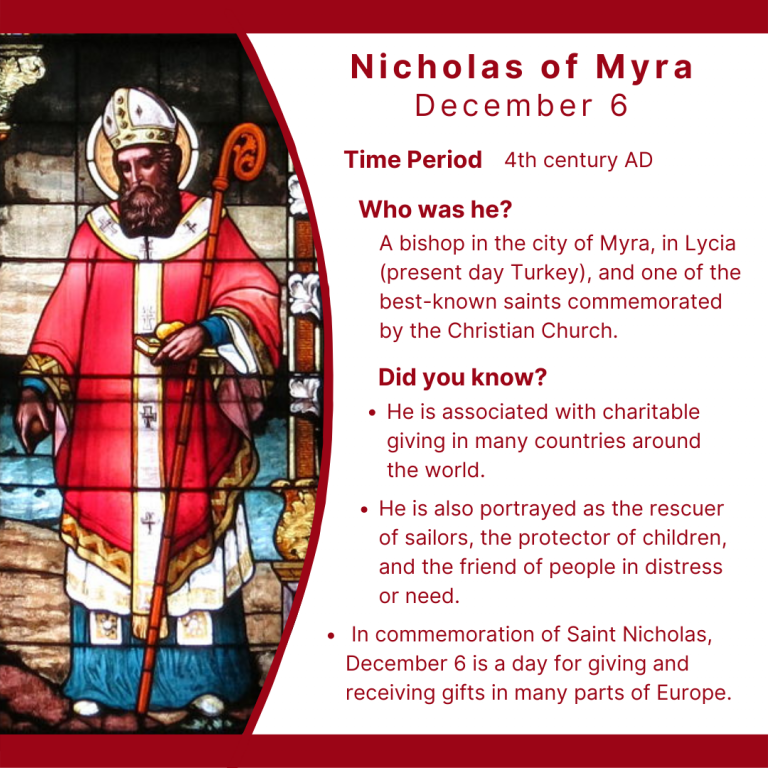

Alien: Covenant begins with a prologue scene between two characters first introduced in Prometheus: Peter Weyland, the multi-billionaire philanthropist who is funding space exploration, and his personal creation David, a highly-advanced android with artificial intelligence. The scene shows David’s activation. The android sits in an ornate chair in a white room overlooking a bleak landscape through a massive picture window. To one side of the android is Piero della Francesca’s painting, “The Nativity” (1470-1475) in which the Virgin Mary and singing angels look down upon the infant Jesus as Joseph converses with two shepherds. On the other side is a black Steinway piano. Behind the android is Michelangelo’s famous Renaissance marble sculpture of King David (1501–1504).

It is this setting the android is activated by his creator Weyland (who he calls father); chooses his own name, David; plays Wagner’s “Entry of the gods into Valhalla” on the Steinway; and asks Weyland the crucial question, “If you created me, who created you?” Then Wayland answers “Ah, the question of the ages… which I hope you and I will answer one day. All this … wonders of art, design, human ingenuity, all utterly meaningless in the face of the only question that matters. Where do we come from? I refuse to believe that mankind is a random by-product of molecular circumstances. No more than the result of mere biological chance. No! There must be more. And you and I, son, we’ll find it.” This conversation undergirds Alien: Covenant and provides an additional framework for the whole franchise.

What follows in Alien: Covenant is the story of a colony ship “Covenant” filled with colonists and human embryos headed for a potentially habitable planet. The ship is controlled by an artificial intelligence named “Mother.” Maintenance and supervision of the ship and its cargo on the long journey is facilitated by an android named Walter, a newer version of the David android. After an accident damages the ship and kills the captain and a number of colonists, Walter brings the crew out of stasis to make repairs. While working on the ship they pick up what they assume is a potential human distress signal from another planet. The planet is close by and looks even more promising than the one they were going to. The new captain Oram, described as a man of faith, decides to change course and investigate the signal over the objections of his second-in-command Daniels.

The planet turns out to be the destination to which Dr. Elizabeth Shaw and David had plotted a course at the end of Prometheus. It is the home world of an alien race referred to as the Engineers. In Prometheus it is asserted that the Engineers had created human life on Earth via genetic engineering and also created a kind of alien life form which becomes the pathogenic antagonists of the film series. Watching Alien: Covenant, viewers begin to wonder, “Will questions raised in Prometheus be answered?” The answer is not really. Something terrible has happened on the planet killing the entire population of the Engineers. It seems that apart from the dangerous Xenomorph alien, David the android is the only living thing on the planet and he’s not volunteering many answers.

The android David stands in front of Piero della Francesca’s painting “The Nativity” in the prologue to Alien: Covenant.

Along the way all the typical Alien tropes unfolds: people become infected one by one; the Xenomorph aliens gestate inside infected people before bursting out and trying to kill everyone else. There’s lots of running around and gunfire, and eventually only a couple of people are left (that all said, viewers who loved 1986’s Aliens will likely be underwhelmed by this film). Where this movie really differs from other films in this franchise is in its focus on the relationship between the two androids, Walter and David, both played by Michael Fassbender. Newer models like Walter were made to be more subservient and less creative. David’s ability to be creative provides the film with its drama and forward momentum.

It turns out he has tinkered with the Xenomorphs genetic design shaping and molding them into his own creation. He wants to be father to them as Weyland is father to him. But there is an unexplained psychopathic deficiency in David. His growing antipathy towards humanity has festered during his time marooned on the planet making him the film’s villain more so than the ravenous Xenomorph aliens.

Without some of the big questions Scott asks, the film would most certainly suffer a kind of derivative generic sameness to other Sci-Fi narratives: it could be just another episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation. But the questions posed make the films Prometheus and Alien: Covenant seem like merely an excuse or convenience for Scott to consider his own questions about creation and evolution, God, intelligent design, and the nature of creativity.

From Weyland creating synthetic androids, to the Engineers making their genetically engineered biological life forms, to David further modifying the Xenomorph aliens, this new series of films are about the manipulation of already existing matter; at no point is something made from nothing. This is important for Christian viewers to consider in light of the first article of the Apostles’ Creed and its explanation from Luther’s Small Catechism:

I believe in God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth. What does this mean? I believe that God has made me and all creatures; that He has given me my body and soul, eyes, ears, and all my members, my reason and all my senses, and still takes care of them. He also gives me clothing and shoes, food and drink, house and home, wife and children, land, animals, and all I have. He richly and daily provides me with all that I need to support this body and life.

He defends me against all danger and guards and protects me from all evil.

All this He does only out of fatherly, divine goodness and mercy, without any merit or worthiness in me. For all this it is my duty to thank and praise, serve and obey Him.

This is most certainly true.

Christians believe that they and all people are creatures of a Creator, who we confess as the Triune God (Father, Son and Holy Spirit); therefore the Christian’s vocation is to act as stewards of the gift of creation. With faithfulness and thanksgiving to the one who entrusted them with the responsibility, a steward preserves and protects what they have been made responsible for, and must work to avoid the hubris of thinking themselves better than their master.

What Alien: Covenant delves into are the horrors that can follow in the wake of dissatisfaction with, or disbelief in, the Creator—when created beings make themselves the ultimate arbiter of what is right and wrong. In the prologue scene David is presented as a sort of Christ like character; he turns out instead to be an anti-Christ. Scott foreshadows this in the prologue itself. After Weyland says to David that he hopes the two of them can find the source of life, David responds: “Allow me then a moment to consider. You seek your creator, I’m looking at mine. I will serve you, yet you are a human. You will die and I will not.” David sees his “advantage” over Weyland and it is a seed of destruction.

Alien: Covenant delves into are the horrors that can follow in the wake of dissatisfaction with, or disbelief in, the Creator—when created beings make themselves the ultimate arbiter of what is right and wrong.

Alien: Covenant provides an opportunity to contemplate the impermanence of humanity’s creative achievements and the horrors borne of the arrogant disregard for others that accompanies atheism and/or a psychotic superiority complex. At one point David is asked, “What do you believe in?” His answer is, “creation.” David believes in the creation but not in the Creator. For Christian viewers the film provides an opportunity to consider the problems that could arise as a result of research into artificial intelligence and genetic modifications of biological life forms (including humans). Where does morality and faith fit into that work? How might such work be influenced by the ideology and personal beliefs of the researchers? When viewed from this vantage point, Alien: Covenant becomes a cautionary tale. The horror is not so much found in the unknown reaches of the dark cold void of space as much as in the human heart.

In the film, David is simply an extension of Weyland, a manifestation of the heart of his “creator.” Remember what Jesus says: “What comes out of a person is what defiles him. For from within, out of the heart of man, come evil thoughts, sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, coveting, wickedness, deceit, sensuality, envy, slander, pride, foolishness. All these evil things come from within, and they defile a person” (Mark 7:20-23). In Alien: Covenant, such evil arises in the character of David.

Scott dedicated his 2014 film Exodus Gods and Kings to his younger brother Tony, who had committed suicide. Alien: Covenant is dedicated to producer Julie Payne who died of cancer in 2016. She had worked for Scott on films like 1991’s Thelma & Louise, 1997’s G.I. Jane, and 2000’s Gladiator. These kinds of dedications reveal that Scott is seriously thinking about mortality, legacy, life and death—and perhaps even life after death and the existence of God. Christian viewers of his films may find this brings an additional interesting element to his work.

Alien: Covenant is an R-rated horror film and viewers will want to be aware of that as they think about watching it. Obviously, this is not a film for children and may in fact not be a film for many adults! While derivative in parts, this new entry progresses the franchise’s unfolding narrative, driving the plot closer to the original 1979 film with more internal than external horror. This is one of those films that may get better in analysis after leaving the theatre. In this case, Scott has made a film where there is more to think about than there is to see.

———————

Rev. Ted Giese is pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church (Regina, Saskatchewan). He is a contributor to Reformation Rush Hour on KFUO AM Radio, The Canadian Lutheran, and the LCMS Reporter, as well as movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. Follow him on Twitter @RevTedGiese.