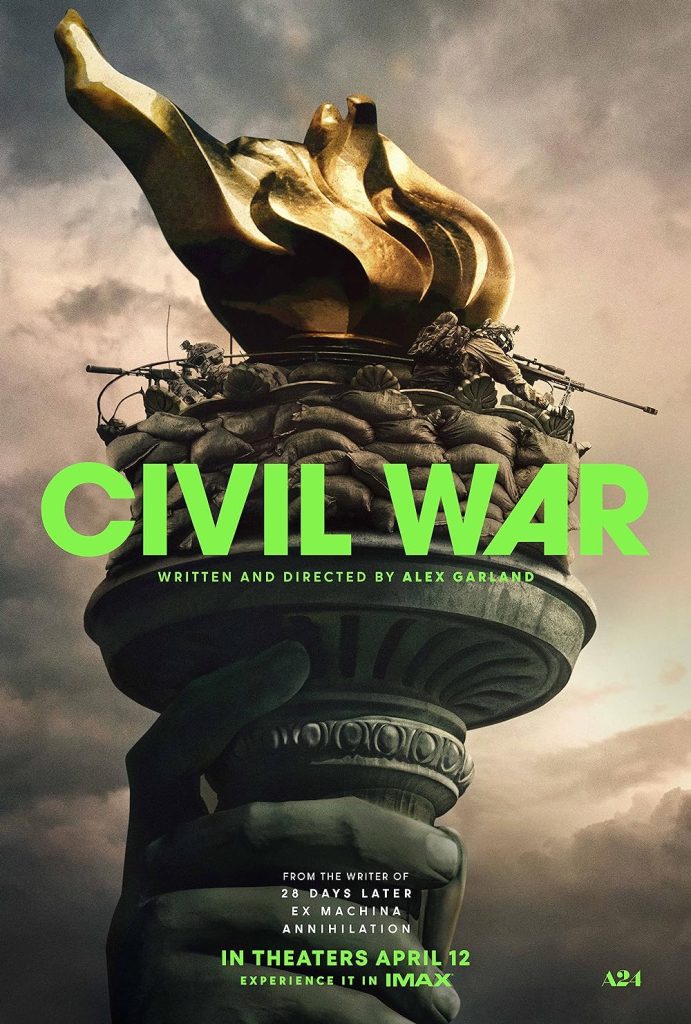

Civil War: A Measured Warning

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

In the not-too-distant future, the states of California and Texas succeed from the union and wage a civil war against the United States government and a beleaguered America. This is the setting of the film Civil War.

No back story is provided to explain why the United States has fallen into civil war; viewers are simply dropped into the conflict midstream as novice fledgling photojournalist Jessie worms her way into joining veteran photojournalist and foreign war correspondent Lee and her reporter colleagues Joel and seasoned rival Sammy on a perilous road trip to Washington D.C. Their goal is to interview the besieged President, a story Joel describes as the last story that matters.

The film’s road trip structure provides the opportunity for a series of vignettes. These brief episodes show a divided America filled with struggling people—ranging from the apathetic to the opportunistic—where political ideals are hardly discussed, and everyday life has been put on hold. Sometimes people are shown engaged in violent encounters where it’s unclear who they are fighting for or against.

Aside from a quotation of the American Pledge of Allegiance and political platitudes like “God Bless America,” there are next to no references to God or discussions of faith in the film. Characters don’t even use blasphemous swears involving the name of Jesus or God, and few if any church buildings are shown dotting the landscape. Keen observers may notice a cross necklace worn by one of unpleasant characters that populate the film, but this is nothing new in Hollywood films. Apart from the elderly reporter Sammy asking Lee if she’s having an existential crisis, there’s little conversation beyond the characters’ immediate situation. Where bigger picture concerns come into play, they tend to revolve around the value of the vocation of journalism in society and not around matters of faith in the face of death. At one point, Jessie reflects on the dangers she’s faced while traveling with Lee and Joel. “I’ve never been so scared in my entire life,” she says. “And I’ve never felt more alive.” Her thoughts are focused solely on her present experience and feelings.

One notable moment of religious content comes when the travellers become trapped in a standoff at a garish ‘Christmas’ themed golf range. An instrumental version of Silent Night plays over a loudspeaker as they duck for cover. With no words being sung, only Christians and others familiar with the lyrics will understand the reference. The military fatigues, the cheap Santa Clauses, and other plastic decorations and ornaments all ring hollow as the bullets fly—and Lee zones in on a small flower growing unaware of the situation surrounding its pretty blue petals.

America’s social ‘religion’ of sports also receives little attention. Garland is careful not to lean too hard into iconic images of mom, baseball, and apple pie. He provides few references to that part of American life. There’s a Pittsburgh Steelers NFL reference spray-painted onto an overpass juxtaposed with victims of public hangings left for motorists to see as they drive. And there’s an abandoned high school football stadium engulfed in urban graffiti being run as a sort of refugee camp by an NGO in which the journalists spend a short time. These bits and pieces of life before the civil war are depicted as sad reminders of the past—a past that seems far distant in the rearview mirror of their lives. After stumbling upon a town seemingly untouched by the conflict and spending a couple minutes shopping, Lee says to Sammy something to the effect of “It’s everything I thought I’d forgotten.” Sammy replies, “Funny I was going to say it’s everything I remember.” The truth of the moment is revealed when Sammy points out men with firearms guarding the streets from the rooftops.

These kinds of images in Civil War—while jarring and arresting—are still familiar to audiences. A quick perusal of current social media or the mainstream media will garner a never-ending series of images of war-torn cityscapes, human cruelty, and war crimes across the world; but it is unsettling to see these modern images and scenes set in the United States, even more so for American audiences. This is an anti-war film that avoids the kind of romanticization which could stoke the viewers’ desire for bloodlust. Given the ominous and apocalyptic imagery running through the film, Christian viewers will want to remember what Jesus says about future troubles in the world, “When you hear of wars and rumours of wars, do not be alarmed. This must take place, but the end is not yet. For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom. There will be earthquakes in various places; there will be famines. These are but the beginning of the birth pains” (Mark 13:7–8). In the midst of these troubles Jesus, advises Christians to “be on guard,” because in such times persecutions of the faithful will increase.

This is an anti-war film that avoids the kind of romanticization which could stoke the viewers’ desire for bloodlust.

One of the most distressing moments in Civil War comes at the muzzle of a gun, when a soldier caught in the act of filling a mass grave, demands to know “what kind of American” each of the journalists identify as. The wrong answer will result in instant death. As unnerving and unsettling as this is, Christians can take comfort in Jesus’ words, “I tell you, My friends, do not fear those who kill the body, and after that have nothing more that they can do” (Luke 12:4). Rather, Christians are taught to place their trust in God who has dominion over body and soul, and who promises them the resurrection of the body and eternal life. Such comfort isn’t meant to encourage foolhardy behavior or reckless living, but rather to give Christians peace in the face of physical death.

This harrowing encounter with the soldier hints at xenophobia as a reason for the civil war but, again, this is never stated explicitly. Xenophobia—an obsessive distrust of “foreigners”—is not something Christians should embrace. Christians are charged with spreading the good news of Christ Jesus to people from every nation, tribe, and language without exception (John 3:16, Matthew 28:19, Revelation 7:9). The broken nature of the conflict creates an underlying question that crackles with each interaction throughout Civil War: whether your neighbour is someone right next door, someone down the street, or someone within the region or nation, how should that neighbour be treated? The Christian has something to say to this: “You shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Matthew 22:39). “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44). “Do good to those who hate you” (Luke 6:27).

Of course, saying words like this while looking down the barrel of a gun can be perilous. In life and death situations, like the ones depicted in Civil War, ethical questions of self-defence and self-preservation become paramount for both Christians and non-Christians. Throughout the film, characters succeed and fail at caring for the physical needs of their neighbours, even risking their lives to ensure others might not die. There are a couple of standout moments where the film confronts viewers with unspoken encouragement to live virtuous lives of purpose—especially if someone died to secure your second chance at life.

One of the positive elements in the film is Lee’s willingness to eventually display sacrificial love towards Jessie. This is not necessarily a religious allegory but rather an acknowledgment that Lee, against her initial judgement of the young girl, grows to see Jessie as the flip side of herself. As such, she comes to see her as someone worth surviving into the future. Deep in this realization is a kernel of hope in the face of hopelessness.

Putting aside public angst in the United States in the months leading up to the 2024 presidential election, Civil War may in fact have less to say about the current American political landscape than it has to say about the ugly nature of war in general and civil war in particular. If there’s something positive Americans can take from the film—the film is set, after all, in America—it may be its depiction of the dangers of polarization and heading down the path which leads to such civil war. It may also encourage sober second thought on the practice of stoking discontent in foreign counties, or championing the causes of foreign conflicts.

A film like this is not for all audiences; the content is brutal and at times dehumanizing—but that’s the point. It is a cautionary piece of filmmaking. The director Garland here sets excuses for combat and conflict, instead zeroing in on the real-world dangers of man’s capacity for self-justification and violence. Lee says to the veteran reporter Sammy: “Every time I survived a war zone, I thought I was sending a warning home: Don’t do this… but here we are.” She used to be a foreign war correspondent but now finds herself in the midst of a war in her own country. This is the core fiction of the film. May it, by the grace of God, remain fiction.

———————

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church in Regina, and movie reviewer for Issues, Etc.