History of the Reformation: The Excommunication of Luther

Luther burns the papal bull. (Detail from 19th century lithograph by H. Schile, after the original of H. Brüchner.)

by Mathew Block

What began in 1517 as a theological argument over the nature of indulgences quickly kindled to far greater flame. By July 1519, Luther was publicly denying at the Leipzig Debate that the pope (or councils, for that matter) had authority to create new doctrines of faith. Scripture alone, he argued, had that power. He was also defending Jan Huss, who had been burned at the stake in 1415 as a heretic for denying the primacy of the pope, among other supposed errors.

This was enough for John Eck—Luther’s opponent at the debate in Leipzig—to declare Luther a heretic too and agitate for his excommunication. To that end, Eck made his way to Rome to join a papal committee charged with examining Luther’s writings. While some on the committee—Cardinal Cajetan, for example—encouraged a careful point-by-point analysis and response to Luther’s works, Eck favoured a simpler approach: condemn Luther’s works as a whole, without bothering to respond to his arguments.

Eck’s approach won out. Forty-one theological points by Luther were identified as “heretical, false, scandalous, or offensive to pious ears, as seductive of simple minds.” Which were “heresy” and which were merely “offensive” were not identified—perhaps even the committee members themselves could not agree. But they were all nevertheless included in a bull issued by Pope Leo X which threatened Martin Luther with excommunication. “By the authority of almighty God, the blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, and our own authority, we condemn, reprobate, and reject completely each of these theses or errors,” Leo X wrote.

“Moreover,” he continued, “because the preceding errors and many others are contained in the writings of Martin Luther, we likewise condemn, reprobate, and reject completely the books and all the writings and sermons of the said Martin.” Everything Luther wrote was to be collected and consigned to the flames. Luther himself was to be given sixty days upon receiving the bull to recant or suffer excommunication.

The bull was promulgated on June 15, 1520, but it would be October 10 before Luther himself would see it. In the meantime, Luther continued preaching, teaching, and writing. And the things he wrote now were far more critical of the Roman church than anything to date. His influential treatise The Babylonian Captivity of the Church is particularly caustic. Here Luther blasts the Roman church for misunderstanding the nature (and number) of the sacraments, and in so doing effectively holding the sacraments hostage from the people. The way in which the sacraments were conducted in the Roman church tended to encourage the recipient to rely on their own merit or works, he argues. But the sacraments were actually given by God with the promise of mercy, to be received by faith.

It is not mere anger which leads Luther here to publicly and explicitly connect the Roman church with the spirit of antichrist. “Unless they will abolish their laws and ordinances, and restore to Christ’s churches their liberty and have it taught among them, they are guilty of all the souls that perish under this miserable captivity, and the papacy is truly the kingdom of Babylon and of the very Antichrist.”

Luther isn’t exactly calling Pope Leo X himself the Antichrist—at least not in the sense people today regularly associate with the term. But he is asserting that the office of the papacy was acting contrary to the will of Christ. That’s what the word antichrist literally means: “against Christ.”

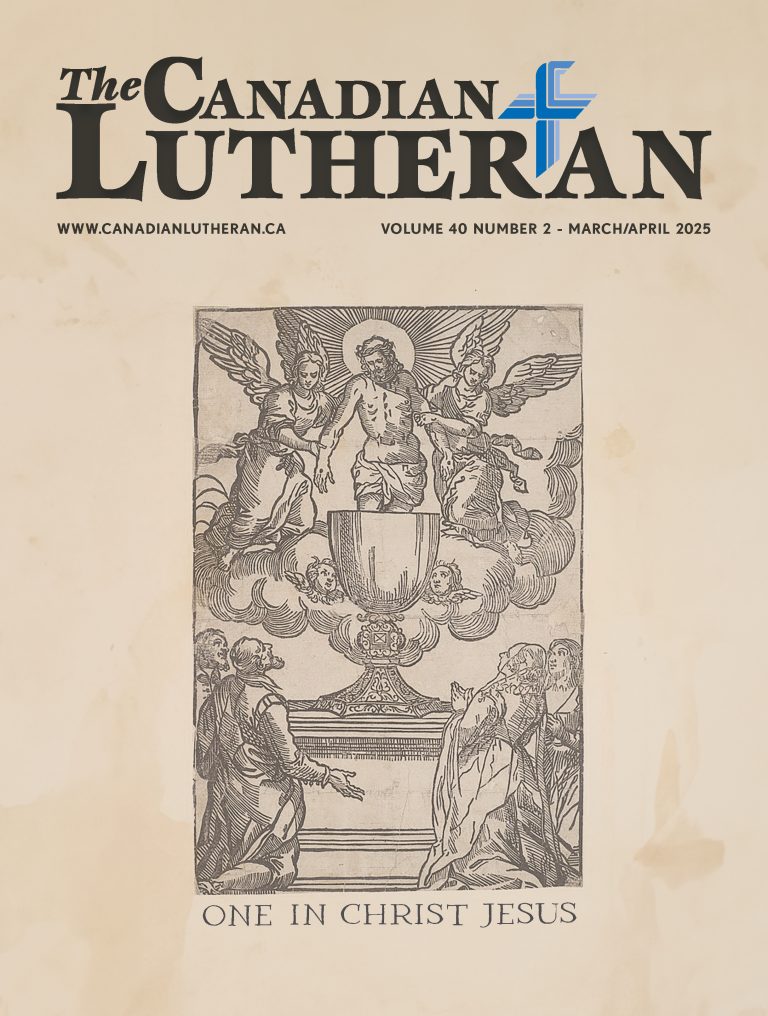

Pope Leo X officiates at a 1521 burning of Luther’s works. (Late 18th century woodcut).

While Luther wrote, the papal bull spread throughout Europe. And true to the pope’s command, the works of Luther began to be burned. In October 1520, the city of Leuven burned eighty copies of Luther’s works. A subsequent burning took place in Cologne on November 12, and another in Mainz on November 29. More book burnings would occur in the months and years to come.

It was not merely Luther’s writing in danger of being burned, of course. Censure as a heretic was a death sentence. The papal bull itself hints at this: one of the ideas for which Luther is condemned is his statement that burning heretics is contrary to the will of God. The implication is clear: recant or face death.

But Luther could not recant. Many of the things for which he was being censured—the teachings for which he was being condemned—were clearly taught in the Scriptures. They were, in short, the Word of God. To deny them would be to deny Christ. That in itself would be antichrist.

“This bull condemns Christ Himself,” Luther laments in a private letter a day after receiving the papal bull. “Now I am certain that the pope is Antichrist.”

Luther burns the papal bull. (Detail from 1872 painting by Paul Thumann).

He would say the same publicly. “Whoever wrote this bull, he is Antichrist,” Luther asserts in a quickly written tract. Even now he is not quite willing to believe it was the pope, and not John Eck, who had written the bull. Regardless, he declares himself ready in the power of Christ to resist the antichristian message it carried. “You then, Leo X, you cardinals, and the rest of you at Rome, I tell you to your faces,” he writes. “If this bull has come out in your name, then I will use the power which has been given me in baptism whereby I became a son of God and co-heir with Christ, established upon the rock against which the gates of hell cannot prevail. I call upon you to renounce your diabolical blasphemy and audacious impiety, and if you will not, we shall all hold your seat as possessed and oppressed by Satan, the damned seat of Antichrist.”

A gentler response to Pope Leo X came a few weeks later as a preface to a new tract On the Freedom of a Christian Man. But even here Luther denies the authority which the pope declared his by divine right. “They err,” Luther writes, “who put you [the pope] above a council and the universal church. They err who make you the sole interpreter of Scripture.”

Sixty days after receiving the papal bull, Luther made his ultimate response. On December 10, 1520 Luther—joined by faculty and students of the University of Wittenberg—assembled outside for a bonfire of his own. There Luther threw the bull to the flames, while others added books of canon law and other works which had obscured the Gospel of Christ.

Luther explained himself simply: “Since they have burned my books, I burn theirs.” Pope Leo X retaliated by officially excommunicating Luther on January 3, 1521.

The fires of the Reformation were set to engulf the whole word.

———————

Mathew Block is communications manager of Lutheran Church–Canada and editor of The Canadian Lutheran magazine.

Some of Luther’s words above are according to Roland Bainton’s translations in Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (1950).

This is part two in a six-part series on the History of the Reformation. Find all the currently published articles here.