History of the Reformation: The Heidelberg Disputation

On April 25, 1518, about half a year following the publication of The 95 Theses, Martin Luther presented at a debate during a meeting of the Augustinian order in Heidelberg, Germany. Here Luther moved away from the question of indulgences into deeper subjects: the question of how we are saved. In The Heidelberg Disputation and its accompanying explanations, Luther made clear he no longer trusted in works righteousness as a road to salvation. Salvation must come instead through Christ alone.

The disputation is best remembered for articulating the difference between the “Theology of the Cross” and the “Theology of Glory.” The former sees all things through the cross of Christ; the latter seeks out the hidden things of God as if they were something we could grasp through our own reason. But trying to understand God in the strength of our own reason, Luther says, inevitably leads to an errant view of God and salvation.

Theology of Glory

Luther explains that those he calls “theologians of glory” believe humanity is more or less still capable of seeking out God on its own. They might recognize that the Fall into sin had negatively impacted the world, but all we really need, they would say, is a little help from God to get back on the right track. In such a system, human reason is placed on a pedestal, and trusted to figure out both who God is and how to approach Him.

Inevitably, this self-trust leads people to place their confidence in their own good works and in their own right thinking in matters of salvation. The theologians of glory in Luther’s day taught that Christians were simply required “to do what is in you” (facere quod in se est) before they would receive grace from God. By “doing what is in you,” they meant Christians had to take the first step towards God—to turn to Him and will themselves to love Him to the best of their abilities. Only after that would God grant them grace.

The theologian of glory thus diminishes the seriousness of human sin downplaying the consequences of the Fall and arguing that human will and works can bring us towards God. Whatever larger role God might play, the theologian of glory nevertheless leaves some part of the work of salvation to himself.

But Luther knew the cross leaves no such possibility. If salvation were merely a matter of “doing what is in us,” then the death of Christ would never have been necessary. At the cross, God reveals exactly what “is in us.” Sin. Death. Decay. Something so heinous, so terrible, that only the death of God Himself can rectify the situation.

However good our earthly works might seem, they cannot save.

We must be honest with ourselves about the predicament we are in, Luther writes. “The theologian of the cross calls a thing what it actually is” – and when it comes to our sin, “it” is not good news. We are sinners through and through. Not even our best attempts at loving God or holy living can save us. However good our earthly works might seem, they cannot save. In fact, they are riddled with sin. “Although the works of man always seem attractive and good,” Luther writes, “they are nevertheless likely to be mortal sins.” The Prophet Isaiah says much the same when he writes, “All our righteous acts are like filthy rags” (Isaiah 64:6).

The yeast of sin is worked too well through the whole dough contaminating everything. So even when we try to obey God’s Law, we offer up polluted sacrifices. We are slaves to sin and even our purported “free will” is corrupted by it! “Free will, after the fall, exists in name only,” Luther writes, “and as long as it does ‘what it is able to do,’ it commits a mortal sin.” Whatever the theologians of glory might say, “Doing what is in you” just won’t cut it. Left to our own devices, we must inevitably be damned.

That thought should drive us to our knees in despair. But that despair is not necessarily bad, so long as it leads us to look outside ourselves for salvation in Another. “It is certain that man must utterly despair of his own ability before he is prepared to receive the grace of Christ,” Luther explains. It is only in recognizing our utter sinfulness that we are ready to “fall down and pray for grace and place our hope in Christ in whom is our salvation, life, and resurrection.”

Theology of the Cross

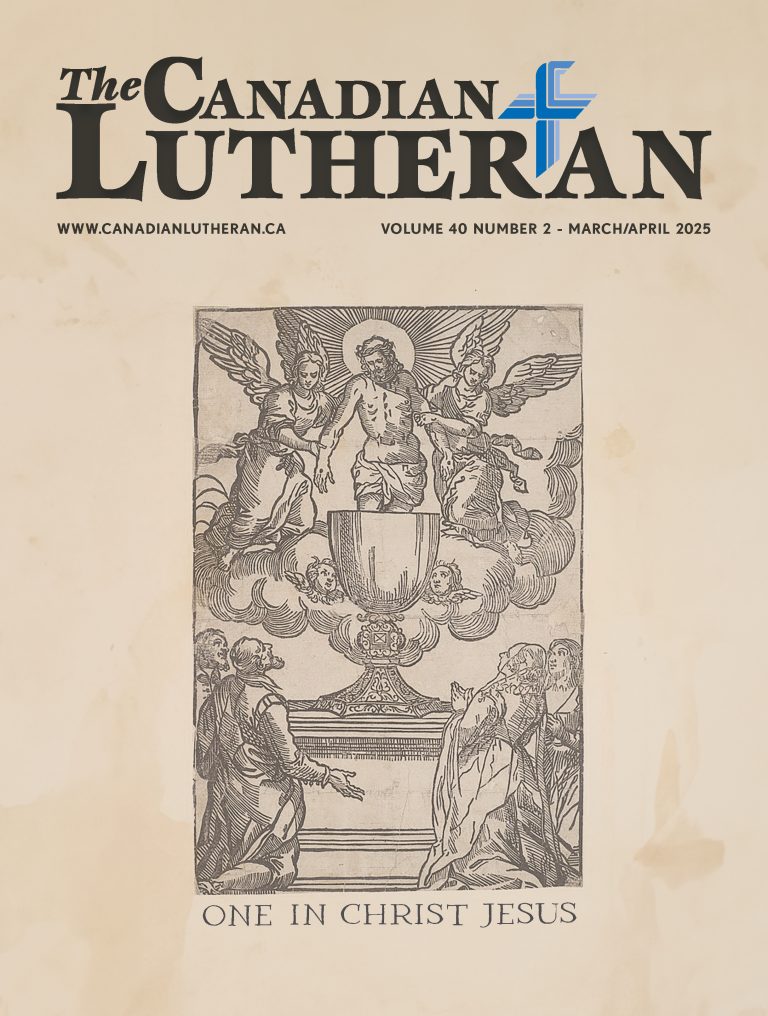

In contrast to the theology of glory, which trusts in human strength, the theology of the cross emphasizes the weakness of humanity. It stresses that we cannot know God on our own terms; instead, we must meet Him solely through His self-revelation in Christ crucified. At Golgotha God reveals Himself in a way we could never have expected. He becomes human and suffers death on a cross. The theologian of the cross must thus learn to disregard outward appearances and trust instead in the works of God, even though—like suffering—they are unattractive on the surface. He must despair of himself and look for salvation solely in the “foolishness of God”— that strange and seemingly inglorious death of God on a tree.

Grace says, ‘Believe in this,’ and everything is already done.

Salvation, then, is something we receive but do not earn. Something we are given but do not deserve. Something that comes by faith and not works. “He is not righteous who does much, but he who, without work, believes much in Christ,” Luther writes. “For the Law says, ‘Do this,’ and it is never done. But Grace says, ‘Believe in this,’ and everything is already done.”

This is good news! The recognition that God saves us through faith in Christ and not our works represents significant growth in Luther’s understanding of the Gospel. But while he points us in the right direction in The Heidelberg Disputation, Luther does not flesh out the nature of salvation in detail. Some may argue whether he yet grasps the Gospel entirely.

One might almost read Luther in this work as saying it is our self-effacement before God that makes Him grant us grace. He writes that “through humility grace is acquired,” (that is, through our self-humility in recognizing our utter sinfulness.) And again: “Humility and fear of God are our entire merit.” These words echo in part the “self-hatred” Luther counselled in The 95 Theses as the right mode of repentance. Taken to an extreme, we might read the early Luther as saying we must hate ourselves as much as God hates sin—which is to say completely—and that we must agree that we are entirely unlovable before He will, paradoxically, make us the object of His love. Luther’s emphasis on terror (of ourselves and our sin) in this work finds no corresponding emphasis on the comfort found in the Gospel.

Consequently, one might say that while Luther identifies the disease of sin and the need for a cure, the good doctor does not quite describe the cure in its fullness. In some ways, this is to be expected: Luther himself dated his breakthrough understanding of the Gospel to early 1519—months after the debate at Heidelberg. But what The Heidelberg Disputation reveals is Luther’s growing understanding that problems in the church were not merely a matter of indulgences. He now understood the whole system of works righteousness was unsupported by Scripture. Good works could not save. Salvation must come from outside the sinner. It must come from Christ.

Luther continues his thinking on this subject in 1519, where he states that “the cross alone is our theology.” For while the crucifixion might seem inglorious, the theologian of the cross knows it to be the foundation of faith. St. Paul said it clearly so many years earlier: “The message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God” (1 Corinthians 1:18).

Mathew Block is the former editor of The Canadian Lutheran

Related Articles