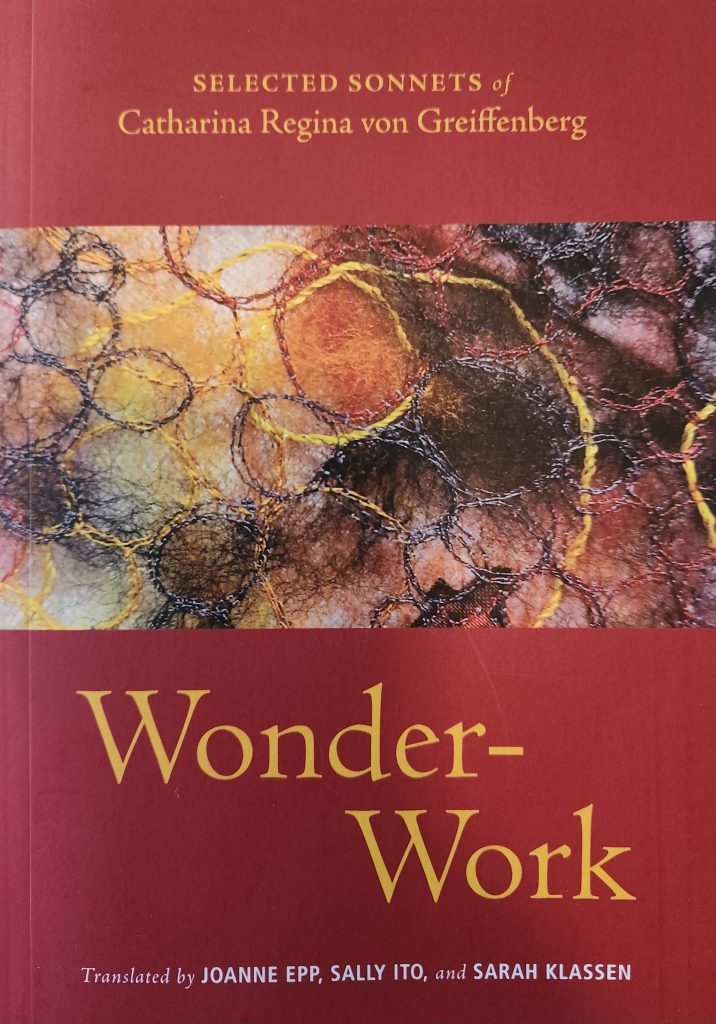

In Review: Wonder-Work: Selected Sonnets of Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg

by Mathew Block

by Mathew Block

The name Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg is not well-known among Christians today, but a recent book seeks to change that; Wonder-Work, published by CMU Press in 2023, features a large selection of sonnets by this Lutheran poet, providing English readers a new opportunity to meet a writer whom the scholar Lynne Tatlock called “the foremost German woman poet and writer in the seventeenth-century German world.”

This new book—a joint translation project by Winnipeg poets Joanne Epp, Sally Ito, and Sarah Klassen—presents 65 sonnets selected from von Greiffenberg’s 1662 book Spiritual Sonnets, Songs, and Poems. The sonnets are arranged according to the liturgical calendar, with a final section dedicated to reflections on God and nature. The translators “have not attempted to preserve the rhyme scheme” of von Greiffenberg’s sonnets, they note, but the translations do reproduce the traditional 14-line structure and “iambic pulse” of the originals. Readers of German will appreciate seeing von Greiffenberg’s original sonnets facing their English translations.

Reading von Greiffenberg’s poetry makes clear both her astute theological understanding of the faith as well as her warm Lutheran piety. She evinces a deep desire for her readers to draw closer to God, but to do by seeking Him in Christ. “Shepherds! Leave the heavens!” von Greiffenberg urges. “Go now to the stable. / Have you ever heard of such amazing wonder-work? / Weakness has borne strength / and a star, the sun.”

The miracle of the God who humbles Himself for our sake—coming down to embrace us where we are, making it possible for us to embrace Him in return—is a recurring theme in von Greiffenberg’s poetry. She marvels that Jesus is “Eternal godhead wrapped in a little cloud: this child. / Just as, from a great distance, the sun / Seems small enough to grasp, so He as God, / Fills everything, yet will Himself be cradled.”

The sonnets on Jesus’ suffering reveal the same theme: the God who leaves the heights of heaven to embrace our sin and shame. “The crown of all angels, Heaven’s jewel and glory” allows Himself instead to be crowned with thorns, she writes. “He who carries all the heavens without pain” bears instead a cross and human sin. Indeed, “He bears not just His own cross, but also me with mine.”

There is a great sense of the blessed exchange at work here; Jesus takes our shame and gives us instead His own blessedness. Or, as von Greiffenberg herself put it: “You endure the barbs and win for me the roses.” “My deepest lowliness,” the Saviour says in another poem, “lifts heavenward.”

In the resurrection, of course, Jesus takes up His place and power anew. Not that He shuffles off the human nature He has assumed on our behalf. No, von Greiffenberg correctly asserts, the transformation of His “body’s suffering into the state of power” sees Him also take His “human nature [into] the glory of the Godhead.” She marvels, “Your omnipotence now shines through your humanity.”

It is precisely Jesus’ assumption of our flesh which allows us to share in the benefits of His death and resurrection. And so, in His tomb, we now “find, not death, but life.”

This is all to say that von Greiffenberg has a strong grasp on theological matters.

This is all to say that von Greiffenberg has a strong grasp on theological matters. But that doesn’t mean these poems don’t also speak to our emotions. For von Greiffenberg, the miracle of salvation is something felt personally and not merely understood: “I feel my heart’s on fire from your words,” she writes. “You rouse and also satisfy desire. / My heart, closed to all but you, my Lord, / rejoices in your risen might and presence.” Her focus on Jesus’ immanent presence in His Words and in the Sacrament—“sweetness from your wounds,” she calls it—gives evidence of a lively Lutheran piety, one worthy of emulation today.

The book includes several sonnets focused on the Lord’s Supper, and here again we see von Greiffenberg’s wonder at the God who comes down to us in humility to meet us where we are. Particularly moving is her sonnet, “The Love- and Wonder-Rich Supper of Our Lord.” “He who made all food now lets Himself be eaten,” von Greiffenberg exclaims. “The one who made both tongue and mouth / descends so low and enters human throats.” “O miracle-rich treasure, endless mystery!” she declares. “I cannot fathom, but I can believe.”

It is of course notable that we are talking about a female poet from the 17th century, a time when not many German woman were writing. But, as the preface to the book makes clear, von Greiffenberg was well-regarded in her day. She was friends, for example, with the prominent poet Sigmund von Birken, through whose support von Greiffenberg’s first book was published. [English-speaking Lutherans today will know von Birken especially for his hymns “Jesus I Will Ponder Now” (LSB 440) and Let Us Ever Walk With Jesus” (LSB 685).]

Von Greiffenberg had a clear sense that lay women like herself, and not only men, were called to give witness to the love of Christ, including through the written word (in addition to poetry, she also published several volumes of spiritual meditations). She reflects, for example, in her poem on “The Revelation, to the Women, of the Resurrection” that it was not to “the sceptre-bearer on the eagle-throne” nor “proud heroes, “scholarly star-seekers,” “white-haired sages,” or “religious leaders” that Christ first appeared following His resurrection but instead “to simple women.” In the same way that they bore witness to Christ, she prays, “let my mouth echo praise for your victory.”

It is only sparingly that von Greiffenberg draws attention to herself as a poet; her ultimate goal is to bring praise to Christ and not herself. “I seek no honour of my own, nor do I deserve it,” she writes in the first sonnet of the book. Should anyone find benefit in her writing, she says, “I beg them in God’s name: do not ascribe to me / the goodness in my words. The eternal one alone / pours goodness into pen and spirit.” It’s a noble explanation of the Lutheran understanding of vocation. Whatever good we do is work that God works through us. And so, von Greiffenberg explains, He alone is worthy of praise.

The final poem of the collection says the same: “O God, your honour I will raise above all else.” But while von Greiffenberg might not seek praise for herself, it is right that we, her audience, give thanks to God for her work (and for the work of her translators!). Through her vocation as a writer and poet—joining words together in “wit, wonder, and delight”—von Greiffenberg gives us words by which we too may pray and meditate on the “Wonder-Work” of our Lord and Saviour. To Him be the glory.

The final poem of the collection says the same: “O God, your honour I will raise above all else.” But while von Greiffenberg might not seek praise for herself, it is right that we, her audience, give thanks to God for her work (and for the work of her translators!). Through her vocation as a writer and poet—joining words together in “wit, wonder, and delight”—von Greiffenberg gives us words by which we too may pray and meditate on the “Wonder-Work” of our Lord and Saviour. To Him be the glory.

———————

Mathew Block is editor of The Canadian Lutheran magazine and communications manager for the International Lutheran Council.