Indigenous people and the Christian faith: A new way forward

So, I’m a white dude. Ironic, I know, given the title of the article. I really struggled with the appropriateness of me writing this piece. One indigenous friend said it was “okay” to do so but he did chuckle at the irony of it all. So, you’re still stuck with the white dude (again!).

Two of my favourite places in the world are Tofino, B. C. and Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in southern Alberta. I have visited them many times. Both sites have been the home to indigenous people for millennia—longer than ancient Egypt. I remember a wonderful experience with a young indigenous guy on the wharf of Tofino. He was talking with some tourists and was saying how much joy he had being an indigenous person—relishing the most beautiful creation around him as his home!

Dances with Wolves in 1990 also made a huge impact on me. It made me think how beautiful indigenous culture is and how we Europeans messed it up. Later in the ‘90s, while doing my doctorate at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, I remember vividly standing at the cloister looking at a poster for a North American indigenous art exhibit being held there. I remember feeling so guilty, and so a part of the problem that I thought I should just stay in my ancestral homeland of Scotland. But without sounding like a psychological rationalization, my blond hair and blue eyes betray the fact that I’m really the product of 9th century Viking raids into Scotland. Genesis 10, the so-called “Table of Nations” which provides the background for the nation of Israel, also makes the point that none of us are of pure genetic or ethnic uniformity. We are all migrants of mixed genetics and ethnicity—and that’s a good thing! This includes the fact that American (North, Central and South) indigenous people are from other geographical and ethnic backgrounds themselves. However, this in no way mitigates the inherent right of first peoples to this land. I also realized there’s no “going back” and that we are all stuck with a complex situation. This is a point my indigenous student will make later when I discuss his MA thesis.

Colonialism

Colonialism is a complex matrix of inter-related ideas such as philosophy, politics and economics frequently embedded in law e.g. the Indian Act. At the core of colonialism, in my view, is pride. It is a veritable “Tower of Babel”. It’s the arrogance and pretentiousness that one culture is superior to another—and therefore presumptively asserts its dominance over other people groups—while stealing their land and resources. This was often possible based on some form of technological advantage e.g. gun power. One should note, however, that Charles Mann in his book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus, has in recent years challenged this notion of technological superiority (firearm targeting was not very accurate during this period!) Mann further argues that European colonization had more to do with the “perfect storm” of circumstances—including plague and famine—which allowed Europeans to prevail over and against overwhelming population odds. In other words: There was no “superiority” involved but simply opportunity. Colonialism goes hand-in-hand with imperialism (sometimes these terms are used inter-changeably). My definition of imperialism is both simple yet essential: “Imperialism is killing other people and stealing their stuff.”

While I understand that some scholars like the African biblical scholar Musa Dube at Botswana University just view the Bible as colonizing, I view the problem as arising from the hermeneutics (interpretive strategies) applied to biblical texts e.g. colonial readings of biblical texts. This perspective can only entangle us in the past and provide no real way forward.

Moving forward requires a realistic acknowledgement of the past in order to deal with it and its fallout.

Post-colonialism

Post-colonialism is a theoretical perspective which “unmasks” and seeks to dismantle colonial power structures. I was first exposed to post-colonial readings of biblical texts at Glasgow University. Specifically, I was exposed to South African biblical scholars who employed post-colonial readings of Chronicles-Ezra-Nehemiah to overthrow and deal with apartheid. In 1994, I was the secretary for the conference on “The Bible in Africa” (another irony). One black South African scholar made a presentation on a “Post-colonial Reading of Chronicles.” In that presentation, he demonstrated how a post-colonial reading of Chronicles may facilitate “truth and reconciliation” in South Africa. Twenty years later, I suggested to my Master of Arts student, Charles Muskego, that he could do a similar thing by using post-colonial readings in relation to indigenous issues here in Canada.

Charles is Dene Suline from Cold Lake, Alberta. He wrote a brilliant MA thesis with me last year entitled Asserting Post-colonial Identities: Cross-Textual Readings of Ezra-Nehemiah and Indigeneity in Canada. There is no way Charles could have written this thesis without his training as a biblical scholar and his three years of experience with Indigenous Relations in the Government of Alberta.

The thesis is a masterpiece, in my view, of how biblical studies and theology can have actual, practical effects in the so-called “real world.”

Like Charles in his MA thesis, I am not going to recount all the horrific things that have happened to indigenous people—because all of that has been well-documented—and because we want to move forward. However, moving forward still requires a realistic acknowledgement of the past in order to deal with it and its fallout. Colonialism is what caused the mass suffering of indigenous people here in Canada, the Americas, and around the world.

I find two amazing things about Charles. One, that he isn’t angrier with the past than he is. I think this is because of his Christian faith, realism, and determination to build a better future for his people here in Canada. But in parts of his thesis one can most certainly detect his annoyance at the Indian Act and Bill C-31. Secondly, I find it amazing that Charles did not abandon his Christian faith. Indeed, I’ve had the privilege to marry him and his wife and baptize their children. Moreover, I find it astonishing, given the abuse that indigenous people have suffered via colonialism (and the wrongly applied version of Christian religion), that 65 percent of indigenous people in Canada remain Christian. This is almost twice the national average.

There are some other surprises in Charles’ thesis. He goes even so far as to be open and fair with the missionary movement—without defending their injustices. He views them as sincere but naively used for colonial purposes and agendas here in Canada by political powers. Charles also gained insight into the complexities of indigenous issues by researching and writing his thesis. The issues are massively complex—and it takes this kind of research to analyze and sort them out in order to come up with working solutions. This will be the focus of Charles’ PhD when he gets around to it.

A new way forward

The number one purpose of Charles’ MA thesis is to provoke a “new way of thinking” about the past, problems and issues. The significance of this thesis is precisely this: It shifts the focus from a negative past to a neutral present for a positive future. I’m sure that positive future depends on a realistic perspective on the past which will give indigenous people a positive future through government policy guided by indigenous peoples’ asserting their self-identity and self-determinism.

The Canadian Centre for Scholarship and the Christian Faith conference for 2018 is on “Indigenous People and the Christian Faith: A New Way Forward.” I believe this is a significant conference for so many reasons. Like Charles’ thesis, and without denying nor trying to mitigate a horrific past, we are stuck unless we move “past the past.” This conference acknowledges the real past but focuses on a “new way forward”.

We welcome all people groups to come and learn and think about how we can all work towards that goal—with love, forgiveness, truth and reconciliation. The conference is an opportunity to dream big and figure out ways to make it happen!

Our keynote speaker is Dr. Cheryl Bear from the Nadleh Whut’en First Nation in British Columbia. She is a faculty associate with Regent College in Vancouver. She and her family, in a camper, have visited more than 600 indigenous communities in both the USA and Canada. She is an award-winning musician too. She will combine her scholarly and musical insight into how indigenous people can heal from the past, act today, and have a bright future with Christian faith. She has a passion to bring the gospel to indigenous people in culturally relevant ways.

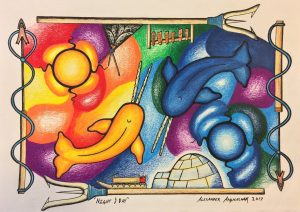

We will also have an exhibit and presentation by Inuit artist Alexander Angnaluak the Governor General of Canada’s recipient for the National Aboriginal Role Model award. He has received many other awards for his life and artwork—including the Historica Canada Indigenous Art Award for his impression of “How the Narwhal Came to Be.” The conference will also feature the artwork of many other indigenous artists. There will be lots of music and the conference will open with indigenous Christian worship.

Please register at https://goo.gl/imNeSJ. There are a limited number of clergy grants to attend free at www.ccscf.org/conference/clergy-grants/ and student grants at www.ccscf.org/conference/grant/.

Rev. Dr. Bill Anderson, an LCC pastor, is director of the Canadian Centre for Scholarship and the Christian Faith at Concordia University of Edmonton where he is a Professor of Religious Studies.