Is The Shack Worth the Trip?

by Ted Giese

Occasionally a product hits the market after interest has peaked and people have moved on. Stuart Hazeldine’s film adaption of the popular 2007 novel The Shack by Canadian author William P. Young may be this kind of product. The opening weekend box office for the film garnered only $16 million US—low for a film based on a book which sold more than 10 million copies. Had the film come out in 2008 it could have exploited the book’s momentum. In 2017, it seems set to fizzle not sizzle—and that’s actually for the best.

Why would that be? For those who followed the story of Young and his book it will come as no surprise that The Shack has come under legitimate theological fire. This is not unwarranted and the film does nothing to change the significant problems.

The Shack is the story of a man, Mackenzie “Mack” Phillips, grieving the loss of his kidnapped and murdered youngest daughter Missy. Although investigators found the crime scene, the girl’s body was never recovered. Later, Mackenzie receives a note in his mailbox inviting him to make a weekend visit to the shack where Missy was murdered. The note is signed “Papa”— his wife Nan’s nickname for God. Could it really be God? Might it be the murderer trying to lure Mackenzie to the scene of the crime? Is it just a sick joke?

Despite a snowstorm, Mackenzie “borrows” his neighbour’s truck and drives to the shack. Initially he finds nothing there except traces of his daughter’s murder which leave him distraught. After almost attempting suicide he has an unorthodox interaction with God. What follows is personal grief counselling from God as Mackenzie deals with his daughter’s death, the problem of evil, and his own troubled childhood in which he was abused by his father. This all happens in a sort of bubble where the ramshackle snow-covered shack is transformed into a summertime paradise complete with an idyllic lake, down comforters, and home-cooked meals served by God.

Depicting God in movies is not new. In 1977, George Burns played God in “Oh, God!” More recently Morgan Freeman portrayed God in Bruce Almighty and Evan Almighty. Unlike these films, where God is largely played for laughs, The Shack attempts a more serious take on the divine.

Sadly, what viewers receive in The Shack is not a faithful depiction of the God of Scripture. It is not the Trinity of the Bible: “one God in Trinity and Trinity in Unity, neither confusing the persons nor dividing the substance,” as confessed by Christians in the Athanasian Creed.

What viewers receive in The Shack is not a faithful depiction of the God of Scripture.

Nor does The Shack adequately present the incarnation of Christ as found in the Apostles’ Creed—where Jesus is confessed by Christians to be “conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary.” Here Christ, as God incarnate, is confessed to be distinctly different from God the Father and Holy Spirit—something The Shack confuses. It’s not enough to have an ethnically-accurate, walking-on-water, wood-working Jesus. If God the Father and the Holy Spirit are depicted incorrectly, and if the presentation of the Incarnation is wrong, then more error inevitably follows.

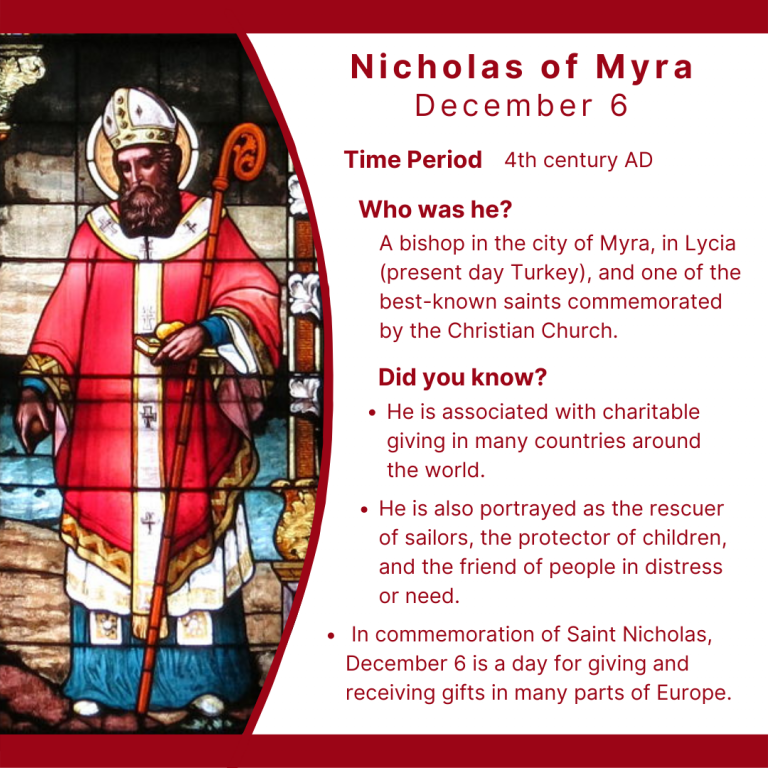

Mackenzie Phillips (Sam Worthington—second from left) along with the The Shack‘s depiction of the Trinity: Jesus (Aviv Alush – left), Papa (Octavia Spencer -second from right), and Sarayu (Sumire Matsubara – right).

In the book and film, Mackenzie interacts with a physical representation of God the Father—a wise/wisecracking black woman happy to be called Papa. Mackenzie likewise interacts with a sensitive Asian woman and gardener, Sarayu, who is intended to be The Holy Spirit. These women are overly affectionate and emotional. Along with Jesus, they are fixated on “relationship” over and against anything resembling religion; Jesus claims to be disinterested in people being Christian at all. The Jesus of The Shack is only interested in people having a relationship with Papa and that relationship is of a certain kind: a sort of endearing intimate relationship often talked about in Pop American Christianity, short on reverence or awe, and capitalizing on society’s emphasis on intimacy in all relationships.

If a discerning Christian compares the intimate relationship Mackenzie has with God in The Shack to the rather impersonal relationship Job has with God in the Scriptural account of Job’s tragic suffering, the difference quickly appears. In Scripture, God’s love for people doesn’t require touchy-feely sentimentality. Ultimately, it requires Christ’s willing sacrificial death in the place of the sinner for the atonement of sin—a death which brings reconciliation between God and humanity. In the Bible, this is the purpose of Jesus’ incarnation and birth, the reason the Word became flesh.

The physical portrayal of God the Father and the Holy Spirit as women muddies what Scripture faithfully teaches about God. But the problem is deeper than Young’s desire to simply overturn the predominate expressions of God in Scripture. Papa claims she appears to Mackenzie as a woman because of his poor relationship with his earthly father who beat him as a child. Later, Papa reappears as a Native American man because Mackenzie needed Papa to be a man when he’s led to his daughters missing body. Since The Shack’s God changes forms, changes masks, to suit the situation at hand, the film actually adopts an ancient heresy on the doctrine of the Trinity: the third century heresy called modalism. This heresy teaches that there is one God who presents Himself in three different modes, rather than the idea that God exists in three distinct persons.

This false teaching becomes abundantly clear in a conversation Mackenzie has with Papa where he accuses God of being bad at sticking close to people in their time of greatest need. When Mackenzie points out that at the cross Jesus asked “My God, my God why hast Thou forsaken Me?” Papa responds, “You misunderstand the mystery.” Papa then shows him nail wounds from the crucifixion saying that she (God the Father) never left Jesus at the cross and that they were “there together,” and that it cost them “both dearly.” Sarayu, the Holy Spirit character, is later seen with the same crucifixion wounds.

This exaggeration of the oneness of God is the old heresy of modalism. The Shack is trying to show how much God cares for Mackenzie’s suffering, but in doing so it undermines the Incarnation itself. Scripture teaches us that, in the Incarnation, God cares so much about human suffering He actually becomes one of us—to suffer and die in our place. But it is God the Son—not God the Father or God the Holy Spirit—who is incarnated. The Shack merges these persons together in the most visual way possible, implying strongly that Mackenzie is not interacting with a God who is three distinct persons, equal in glory, and coeternal in majesty within the Godhead. In the biblical understanding of God, only Christ, because of His incarnation, keeps the wounds of His crucifixion as emblems of His sacrifice (John 20:19-31).

Why is this important? Students of Luther’s Small Catechism will recall a section called “Christian Questions with Their Answers.” It’s a series of questions prepared by Luther for those who intend to go to the Sacrament of the Altar. Question 8 asks: “How many Gods are there?” The answer is: “Only one, but there are three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” Question 9 asks: “What has Christ done for you that you trust in Him?” The answer is: “He died for me and shed His blood for me on the cross for the forgiveness of sins.” Then question 10, a very important question as it pertains to this part of the film, asks: “Did the Father also die for you?” The answer is: “He did not. The Father is God only, as is the Holy Spirit; but the Son is both true God and true man. He died for me and shed His blood for me.”

As soon as Papa shows wounds from the crucifixion, The Shack fails to be a Christian story and embraces the ancient heresy of modalism, an unfaithful depiction of the Holy Trinity and by extension a denial of the incarnation of Christ Jesus as taught in Scripture. The god of The Shack is not the Christian God of Scripture.

As soon as Papa shows wounds from the crucifixion, The Shack fails to be a Christian story and embraces the ancient heresy of modalism, an unfaithful depiction of the Holy Trinity and by extension a denial of the incarnation of Christ Jesus as taught in Scripture

The film includes many other theological problems, which there isn’t room to discuss here. But the fundamental misunderstanding of God gets right to the heart of the problem. This is not a Christian film: It’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing, wrapped in wholesome family values and with a high regard for marriage and parenthood. Mackenzie’s interactions with the god of the The Shack are permeated with the sort of moralistic therapeutic deism which passes as Christianity for many people today. It’s a system of belief which stresses that God simply wants people to be good and nice to each other in the way most world religions and the Bible are presumed to teach, and that the main goal of life is to be happy and feel good about oneself free of unresolved problems.

The whole film becomes a sleight-of-hand which pays lip service to grief and suffering while emptying the cross of Jesus’ true sacrifice for sin, sidestepping the promise of the resurrection and the believer’s hope that rests in Christ alone. Viewers should be careful: the story is a confused and disjointed mixing of truth and falsehood. Even as a work of fiction it is not worth defending.

Yet some might ask? “Can’t terrible stories make for good films?” The answer? The Shack is not a good film. It’s B-grade at best with an unsatisfactory ending. [SPOILER ALERT] While heading home from his weekend in the shack Mackenzie ends up in a major accident. He awakes in the hospital only to be told that the accident happened on his way to the shack and that he spent the whole weekend in the hospital. Did any of his divine interactions really happen? Was it all a dream? Did Papa lead him to his daughter’s missing body? Did he bury her in a coffin hand-made by Jesus the carpenter? Or did it all just happen in his head?

This is the worst kind of film ending and differs from the book’s conclusion where there is a concrete resolution concerning the missing body—something that leads to the real-world capture and prosecution of the killer. In the film no time is spent resolving any of this. Rather, Mackenzie puts his grief behind him and lives a happy life with his family, almost as if nothing bad had ever happened.

Feel free to skip going to The Shack. There is nothing substantial there for the Christian. All you’ll find is a heretical wolf in sheep’s clothing— modalism. And it’s a wolf that will bite anyone who takes their eyes off it for even a moment.

———————

Rev. Ted Giese is associate pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church (Regina, Saskatchewan). He is a contributor to Reformation Rush Hour on KFUO AM Radio, The Canadian Lutheran, and the LCMS Reporter, as well as movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. Follow him on Twitter @RevTedGiese.