Lutherans and the Benedict Option: Charting our way in a post-Christian society

by Esko Murto

To tell a complicated thing in a simple way is better than telling a simple thing in a complicated way. Rod Dreher’s 2017 book The Benedict Option falls into the first category. It is approachable, easy to read, and clear enough, but deals with a topic both important and complex—namely, how the Christian Church can go on in a post-Christian world.

To tell a complicated thing in a simple way is better than telling a simple thing in a complicated way. Rod Dreher’s 2017 book The Benedict Option falls into the first category. It is approachable, easy to read, and clear enough, but deals with a topic both important and complex—namely, how the Christian Church can go on in a post-Christian world.

What’s so Benedictine about the Benedict Option?

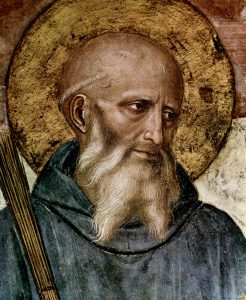

The name “Benedict Option” needs a bit of explaining though—and after that, a bit of more explaining. The Benedict of the title refers to St. Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 – c. 547), often called “the founder of Western monasticism.” At the time of St Benedict, the world of antiquity was coming to its end; the Roman Empire (at least in the West) was being brought down by barbarian invasions from the outside and corruption from within. Benedict, so the story goes, was born into nobility, but chose to live as a hermit after seeing the decadence and corruption in Rome. Over time, he attracted a number of followers, and the Benedictines were born.

Benedictines were the critical link between late antiquity and the medieval age. It was the monasteries that became the depositories of western civilization and Christian faith when the Roman world collapsed. In their studies, monks slowly copied ancient texts, preserved knowledge of sciences, and maintained and developed arts. Likewise monks later emerged from their cloisters and began the missionary work of re-Christianizing Europe.

The Lutheran Church has traditionally held a negative view of monasticism, and at the time of Reformation the monasteries had become both organizationally and theologically corrupt. It’s important to note that The Benedict Option is not encouraging Christians to all become monks and nuns. Nor is this a book which examines the history and theology of the monastic movement. Instead, it simply provides Benedict as an example of Christians finding a way to hold on to their faith and lifestyle even amidst great change in their surroundings.

Fall of the Christian West

What has Benedictine to do with the present day? The Western world is now in a situation similar to that of St. Benedict’s time, with old Judeo-Christian culture collapsing into what appears to be some sort of post-modern barbarism. Instead of drinking mead from skull-cups in loin cloths, this barbarism is characterised by: (1), the abandonment of objective moral standards; (2), the refusal to accept any religiously or culturally binding narrative, except as chosen; and (3), the repudiation of history as irrelevant. It is shallow, whimsical, and subjective.

Dreher contends that the Culture War between secular culture and Christianity in the West has been lost. The Views of the “liberal elite” are already shared by the majority of people, and their ideas are even penetrating Christian churches as well. The Benedict Option is not a book meant to rouse complacent Christians to battle secularism, or to muster together the remaining forces to turn the tide of cultural change. The change has taken place, Dreher says, and it won’t go away—at least, not in the short run. The Judeo-Christian worldview has moved from being the majority to a minority, and increasingly even a marginalised minority.

The old alliance of Christian faith, majority culture, and legislation in the West has come to its end. But that does not mean the end of Christianity. The Church can not only survive, but even thrive.

Is there hope? At the twilight of Ancient Rome, the survival of the Western Civilization became possible when it was no longer connected to the survival of the Empire. The Benedict Option calls the Christian reader to accept that the old alliance of Christian faith, majority culture, and legislation in the West has come to its end. But that does not mean the end of Christianity. The Church can not only survive, but even thrive in the Post-modern era if it accepts this reality and acts accordingly.

Church as a community of truth, beauty, and love

In the Postmodern ear, “truth” and “beauty” are often downplayed as mere opinion. The Church must resist this apathy and embrace not only the doctrines of Scripture, but also seek to rediscover the worldview where these truths become the most important thing in our lives. And if they are the most important thing, then we will desire to express these truths in not only clear, but also beautiful ways, using all arts accessible to us. In our era, traditional apologetics have become in many cases ineffective; but the compelling power of beauty remains. Aesthetics don’t make one into a believer, but they can be the necessary first step that causes people to stop and listen.

“Love” is another way for the Church to show what truth is when rational arguments are ignored by the wider world. Consider the subject of marriage: the Christian view on marriage might not win in a public debate, but when Christian spouses commit themselves to a life of love and faithfulness, they give a testimony to what the Christian understanding on marriage means in practice.

This speaks to the broader importance of our lives as public witnesses to our faith—and to the dangers, consequently, of being lax in our practice of our church discipline. Such discipline is not so much a tool for moral improvement, but rather provides a testimony to the integrity and solemnity with which the Church keeps its truths. The church that claims to teach the Truth but fails to reject falsehoods gives a testimony of relativism, no matter what they claim on paper.

The most interesting and also challenging part of the Benedict Option deals with the Church as a concrete, social community (instead of merely an abstract spiritual idea). This begins in the smallest communal unit: one’s own home. Calling it a “domestic monastery,” Dreher encourages Christian families to consciously make family devotional life a top priority. As a part of the “monastic” nature of home, Christians should practice hospitality but also make clear at least to themselves that their home is a Christian household, with the limitations that brings.

The desire to make Church into a concrete social community, “the idea of a Christian village,” requires work and almost always needs intentional commitment. When so many distractions are competing for their time and energy, Christians need to make a conscious decision to prioritize the Church as their primary community. At the same time, the social reality of the church should not become an idol; the love between members is a fruit, not the foundation, of the life of faith.

In the end, The Benedict Option is not anything radically new. And it does not even try to be. Instead, it encourages Christians to rediscover something the Church has always possessed. At its heart, it is a call for the Church to be the Church. “This Benedict Option thing, it’s just being Christian, right?’” one young woman comments in Dreher’s book. “It’s just the church being what the church is supposed to be.”

The strength of the Benedict Option is its low threshold of application—you do not need much to get started. As Dreher writes, “Don’t let the best be the enemy of good enough.” Start small and make it sustainable from the beginning.

Rev. Esko Murto is Assistant Professor of Theology and Dean of Students at Concordia Lutheran Theological Seminary in St. Catharines, Ontario.

How can you start “being the Church” more intentionally where you are?

- Does everyone know everyone by name in your church? Knowing a name is not much, but that’s where it usually begins. Seek ways to make this happen.

- Is devotional life important in your daily life? Prayer and the study of Scriptures is good for you and your family. How can you make sure you have enough time for it every day?

- Holidays sometimes call us to ask which bonds are more crucial to us: the ones founded on kinship or the ones created by the Holy Spirit. Should you stay home Christmas morning to spend quality time with your relatives if it means missing out on one of the greatest feasts of the Church?

- Can I/we be more hospitable to our unbelieving neighbors as well as brothers and sisters in the Church? “They have a common table but not a common bed” the Epistle to Diognetus from the second century described Christian families.

- How do we, as a congregation, enforce integrity and accountability through the use of church discipline without falling into moralism and judgmentalism?

- How can we give testimony of our faith through beauty in the church—either in the visual arts, music, or other ways? Is it possible to do this without using a lot of money? Or should we try to use money just to remind ourselves of what matters? What does it communicate if you drink wine at home from a crystal glass and the Lord’s Blood at church from a disposable cup?

- People have always needed communities not only for the sake of companionship, but also and especially for mutual support and protection. If someone in our church suffers from sickness, are we going to visit them? If their house burns, are we going to help build a new one? Are we ready to devote real time and money for the wellbeing of our brothers and sisters? Do we even our fellow congregants well enough to know if they were suffering?

- Am I ready to make sacrifices for my faith if needed? It may mean that some hobbies, relationships, or jobs won’t work for me. Can I accept this, knowing that the Gospel is still a treasure that makes me happy and rich beyond measure in heavenly things?