Martin Luther and the Care of Souls

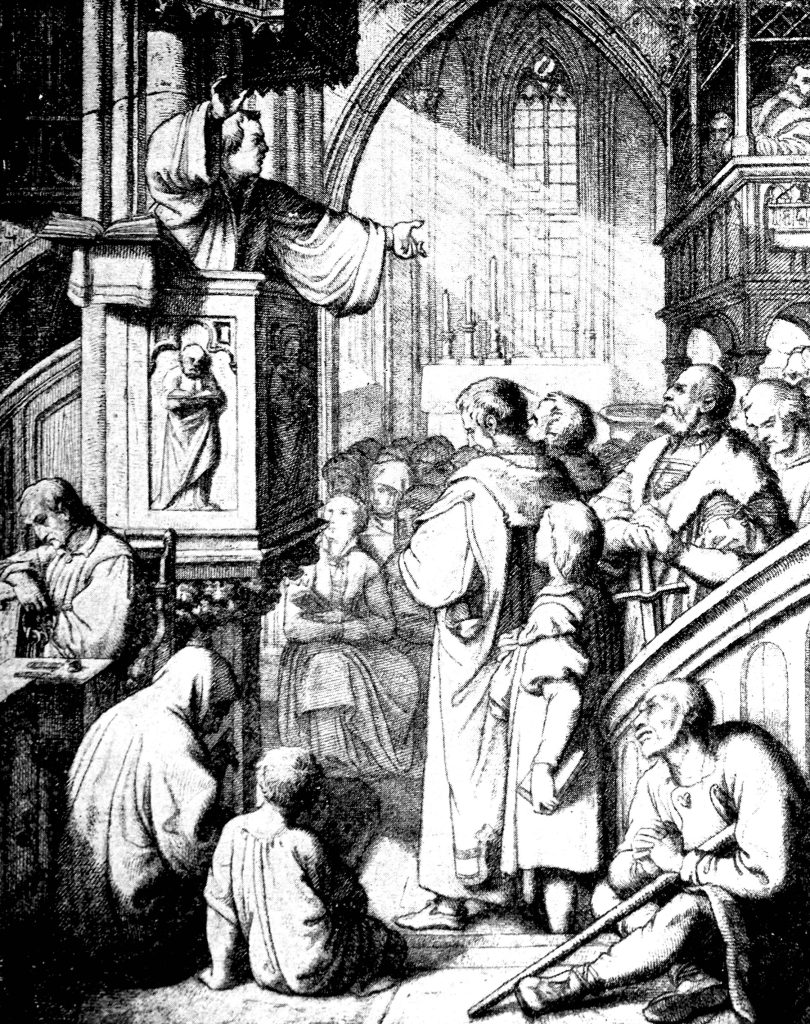

Illustration: Gustav Koenig, 1847.

by John A. Maxfield

The most important thing to know about the reformer Martin Luther (1483-1546) regarding the care of souls is that Luther was above all a pastor—that is, a shepherd of Christ’s sheep. Yet his pastoral care was conducted mostly through public preaching and teaching in the university, and through his writings as a reformer. Beyond his published writings and extensive letter-writing, Luther’s understanding of the care of souls is mostly known for his insights and comments on receiving pastoral care, from his spiritual mentors in the Augustinian convent and especially from his own pastor, Johannes Bugenhagen, who was called in 1523 to be the head pastor in the Wittenberg town church (where Luther was also called as a pastor).

Luther’s pastoral ministry was shaped by his spiritual experience in the monastery (from 1505) as an Augustinian friar (brother), by his service in the priesthood, by his calling to be preacher at the town church in Wittenberg as well as professor of theology at the university, and finally by his activity as a reformer that led to and shaped the Protestant Reformation.

As a friar in the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt and later in Wittenberg, Luther learned by personal experience to care for his own soul as well as for the spiritual life of his brothers in the convent, especially by private devotions and corporate worship. The Psalms played a central role in this devotion, as the psalms were recited aloud continually throughout the days in private prayer (often alone in the friar’s cell), at mealtimes as the friars ate while listening to a brother reading aloud the psalms, and at worship together in the monastery chapel. All 150 psalms would have been recited each week, spiritually forming the brothers through God’s Word as expressed in these age-old prayers of God’s people Israel and of the Church of the New Testament.

In Martin Luther’s writings, the Word of God flows from his memory onto the page as the rich experience expressed in the psalms—from confession of sin to expressions of praise and confidence in God—is lived out in the daily rhythm of Christian life. This personal experience of God’s Word is evident throughout Luther’s career as seen in personal correspondence, his sermons, his lectures on the Bible at the university, and his pastoral writings as a reformer.

Luther was above all a pastor—that is, a shepherd of Christ’s sheep.

Luther is primarily remembered for his work as a reformer of the church, and he engaged the spiritual life of Christians as well as topics of reform through his lectures at the University of Wittenberg. Each of his series of lectures at the university—throughout his career, from 1513 to 1545 (his last lectures, on Genesis 50, given just a couple months before his death)—were devoted to the Bible. Luther used the text of Holy Scripture to teach his students about their spiritual life from God’s own Word. His lectures were more like sermons, using God’s Word in Scripture to form his students spiritually as they were prepared to serve as pastors in churches now being changed dramatically by the Reformation.

Luther was also called to preach in the town church in Wittenberg, and from this pulpit as well as through his published sermons, Luther was continually active in the care of souls. From his very first published writing in early 1517 (a brief commentary in the German language on the seven penitential psalms) to his bursting onto the scene of public life in November 1517 after the

Illustration: Gustav Koenig, 1847.

circulation of his 95 Theses on the subject of indulgences, Luther used written texts—often printed sermons—to care for souls. While the 95 Theses were prepared for an academic disputation—a highly professional and difficult form for debating theological topics as a university professor—Luther was engaging a subject of pastoral care, raising questions about the message being conveyed by preachers who promised, “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory springs.”

Sometime early in 1518, Luther followed up his Theses (written in Latin) with a simple, twenty-paragraph pamphlet written in German and titled: “A Sermon on the Indulgence and Grace.” Here the pastor and professor taught people in a simple way about the problems he recognized in the way the Sacrament of Penance (private confession to one’s priest) was being practiced at the time. As a caretaker of souls (the German word is Seelsorger), Luther was concerned that people were being misled by a very popular practice associated with Penance—namely, that by giving a contribution to the church they could make up for their sins and gain an early (or at least earlier) release from the sufferings or “purgation” of sinful guilt that they (or their deceased loved ones) still owed to a holy God in Purgatory. Out of Luther’s pastoral concerns for the care of souls—largely because those concerns were dismissed and condemned as heresy—Luther’s Reformation developed into a division of the Catholic Church and the Reformation of Christianity.

Luther was the most-published author in his day and, indeed, in history. And of his many writings, his short book Freedom of a Christian best expresses Luther’s concerns for the way the Gospel can bring spiritual comfort to souls troubled by sin and by the various burdens in life experienced by Christians. Luther opens this treatise—which was published in November 1520 before the Reformation really became a movement to change the very character of Christianity—by acknowledging: “Many people have considered Christian faith an easy thing, and not a few have given it a place among the virtues. They do this because they have not experienced it and have never tasted the great strength there is in faith. It is impossible to write well about it or to understand what has been written about it unless one has at one time or another experienced the courage which faith gives a man when trials oppress him.”

Luther shows that faith in Christ frees the Christian believer from the attacks of his or her own conscience because of sin

Through this one short book, the Reformer cared for the souls of thousands of Christians in his own time and millions since, unveiling the meaning of Christian faith and life. Luther shows that faith in Christ frees the Christian believer from the attacks of his or her own conscience because of sin; from false views about salvation (taught in the church of Luther’s day and still today) that make it seem that God’s love and forgiveness is conditioned on our good works; and, finally, from the burdens placed upon us in this world to earn the acceptance and esteem of others by means of our efforts and successes in life. Toward the end of the booklet, Luther concludes with a brief description of what a true Christian is: “A Christian lives not in himself, but in Christ and in his neighbour. Otherwise he is not a Christian. He lives in Christ through faith, and in his neighbour through love. By faith he is caught up beyond himself into God. By love he descends beneath himself into his neighbour. Yet he always remains in God and in his love.”

Five hundred years later, Christians today can still receive Martin Luther’s pastoral care of souls by reading his writings, especially his catechisms, sermons, and lectures on the Bible.

———————

Rev. Dr. John A. Maxfield is Professor of History and Religious Studies at Concordia University of Edmonton, and also serves as an assistant pastor at All Saints Lutheran Church, Edmonton.