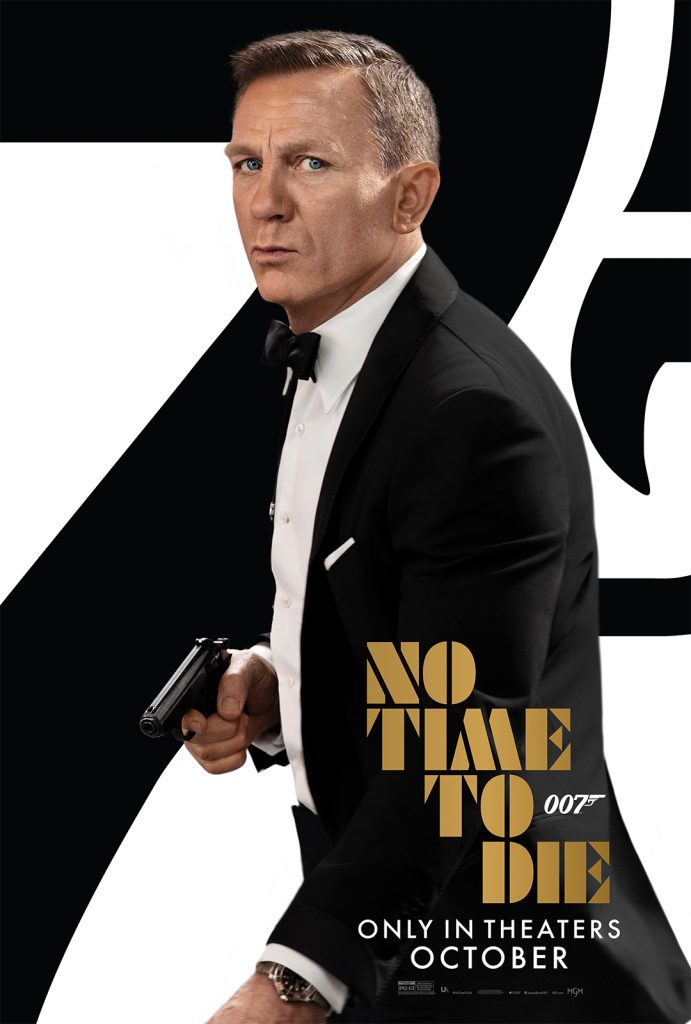

No Time to Die: 007’s Swann Song

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

This is the end. Hold your breath and count to ten. At least, it’s the definitive end of Daniel Craig as James Bond. Following the events of 2015’s Spectre, a short-lived but passionate romance with Madeleine Swann, and dropping so far off the radar that MI6 has presumed him dead, Bond is replaced by Nomi (Lashana Lynch) as the new 007.

Meanwhile, CIA operative Felix Leiter coaxes Bond out of retirement to assist the Americans in a pivotal operation against SPECTRE in Cuba. This sets in motion a reckoning that ties up virtually all the loose ends of this five-part 007 series. The concluding episode centres on repentance, revenge, reconciliation, and retribution. It finds Bond saving the world one last time, as two 007s race to stop the sinister Lyutsifer Safin and his plot to wipe out billions of lives with the targeted spread of a DNA-based viral nanotechnology.

From 2006’s Casino Royal (2006) to 2021’s No Time to Die, the creative minds behind the modern 007 franchise have done something different. They have brought the internal story of James Bond’s psychology and soul into the foreground something the previous 20 films had, with the exception of one film, only hinted at. Each outing of Daniel Craig’s Bond built on the previous film, creating a cohesive story. While previous Bond films had recurring characters, motifs, and criminal organizations, on the whole the events of one film didn’t really impact the events of the next. In the past, recurring elements created a familiar experience; if Bond didn’t order a vodka martini “shaken, not stirred,” or if he didn’t introduce himself as “Bond, James Bond,” or if the signature brassy Monty Norman and John Barry orchestral score with the twang of Vic Flick’s iconic guitar were missing it would hardly be a James Bond film. But for the most part, each Bond film was a clean slate, a new adventure which didn’t necessarily rely on previous films.

Producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson have turned that formula on its head with the last five films, providing both what the audience expects from a Bond film while pulling all the background themes into the foreground—weaving everything together into a single story that can be enjoyed on its own without having seen the previous films. The story begins in 2006’s film with Bond as a green field operative, freshly given his ‘00’ designation. It finishes in 2021’s No Time To Die, with him as a seasoned and skilled agent. They feature a Bond with a clear character arc of self discovery. He is forced to come to terms with his past—an orphan used as a tool of geo-political statecraft—as well as with own tragic failures in judgment when it comes to love. The Craig films invite audiences to ponder two primary questions: Will this broken man find redemption for his failures? Can he get past the failure to save Vesper Lynd from death and truly trust and love again?

In the past, recurring elements created a familiar experience; if Bond didn’t order a vodka martini “shaken, not stirred,” or if he didn’t introduce himself as “Bond, James Bond,” or if the signature brassy Monty Norman and John Barry orchestral score with the twang of Vic Flick’s iconic guitar were missing it would hardly be a James Bond film. But for the most part, each Bond film was a clean slate, a new adventure which didn’t necessarily rely on previous films.

This change of formula, shifting from an emphasis on style to substance, was a gamble and has certainly paid off. The new Bond has been critically lauded as a breath of fresh air for the franchise, but will it pay off with audiences? Many viewers became invested in Craig as Bond, and because No Time to Die definitively concludes this five-part story and answers those initial questions it gives Broccoli and Wilson a clean slate to move forward. Casual viewers who know the well-established Bond formula but have not watched the four films leading up to No Time to Die may end up feeling a bit lost. No Time to Die rewards a good memory of the past Craig films to help keep straight what is going on, who all the players are, and how they relate to each other.

Early in the film James and Madeleine Swann arrive in Matera, Italy during a local festival where people write their secrets on paper and burn them to help let go of the past. Both love birds desire to move forward in their new life together, promising to share their secrets along with the consequences which continue haunting them. The Acropolis in Matera happens to be the final resting place of James’ first love Vesper Lynd who sacrificed herself to help him escape certain death and who James could not save—a tragic turn of events that hardened Bond towards love and exasperated his need to succeed in every perilous situation. Alone at Lynd’s graveside, Bond burns a slip of paper with the words “forgive me” just as a bomb explodes from inside her stone mausoleum. Narrowly escaping and suspecting Swann lured him there to kill him, and feeling betrayed again by a woman he truly loves, Bond puts Swann on a train and tells her she will never see him again. With Bond’s repentant note, Christian viewers may be reminded of the prayer: “Remember not the sins of my youth or my transgressions; according to Your steadfast love remember me, for the sake of your goodness, O LORD!” (Psalm 25:7). The mature Bond’s bid to find forgiveness for his past fails as he falls to the temptation to think the worst of Swann. When confronted by Bond, she pleads “Why would I betray you?” to which he replies, “We all have our secrets. We just didn’t get to yours yet.”

No Time to Die expands on Swann’s secrets. The daughter of SPECTRE operative White, Swann in her youth had been targeted for revenge and forced to defend herself against assassination attempts. Her father (a recurring antagonist first introduced in Casino Royal and a onetime close confidant of Ernst Stavro Blofeld, the head of SPECTRE) had been tasked with eliminating a family of poisoners. He successfully murdered them with their own poison with the exception of a young boy Lyutsifer Safin. The boy grew up, taking on both the family tradition of poison-making and harbouring a burning desire for revenge against the people responsible for his family’s death. This is generational retribution—the sins of the fathers directly impacting the lives of their children. At first Bond’s connection both to Swann and Blofeld—his adoptive brother revealed in Spectre— threaten his life and future happiness simply by making him potential collateral damage in the face of Safin’s plot. But as events unfold, Safin becomes focused on punishing Bond along with everyone else on his hit list.

This may remind Christian viewers of the warning attached to the Ten Commandments in the book of Exodus: “You shall not bow down to [an idol] or serve them, for I the LORD your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate Me, but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love Me and keep My commandments” (Exodus 20:5–6). Devotion to SPECTRE—whose idolatrous emblem is an octopus and where the Ten Commandments are broken regularly—invites just retribution. With this in mind, No Time to Die and the previous four films become a story of how outright and obstinate sin for worldly gain brings tragic results on individuals and upon their children. As a result, White and Blofeld come to ignoble ends and their families pay the price for their sins.

This change of formula, shifting from an emphasis on style to substance, was a gamble and has certainly paid off. The new Bond has been critically lauded as a breath of fresh air for the franchise, but will it pay off with audiences?

From a Christian perspective, as “an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer” (Romans 13:4) Bond is constantly bringing retribution against the plans of SPECTRE while thwarting their endeavours and uncovering their very existence and identities to the governing authorities. Lyutsifer Safin, the maligned orphan, in a twisted way sees himself as a sort of mirror image of Bond. At one point he comments, “James Bond. License to kill, history of violence… I could be speaking to my own reflection.” In this world or the next, Christians believe God will punish unrepentant sin; in the context of No Time to Die, Bond and Safin bring retribution upon evil while pitted against each other. Bond does so lawfully under the authority of the British Crown while Safin does so in a different way.

In his Large Catechism, Martin Luther writes: “if you steal much, you can expect that much will be stolen from you. He who robs and gets by violence and wrong will submit to one who shall act the same way towards him. For God is master of this art. Since everyone [within the criminal element] robs and steals from one another, God punishes one thief by means of another. Or else where would we find enough gallows and ropes?” The problem with Lyutsifer Safin (whose name is a play on Lucifer Satan) is that he thinks of himself as a god not just bringing retribution upon SPECTRE, but upon the whole world.

Safin believes the average person doesn’t really want independence and freedom; they “want to be told how to live and then die when we’re not looking… people want oblivion.” “So here I am” he says, “their invisible god sneaking under their skin.” Bond warns Safin, “History isn’t kind to men who play God.” So while Bond and Safin might start with some shared goals and a similar purpose with respect to ending SPECTRE, Safin’s goal of poisoning billions of unsuspecting people with his DNA-based viral nanotechnology must be stopped. Further complicating the plot and drawing these two men together is their personal histories and current interest in Swann. Bond ends up seeing her as his hope for a life free from espionage; Safin sees her as a twisted kind of personal reward, a prize he deserves because he once saved her life. Swann would either be a gift willingly received by grace in love or ill-gotten gains stolen and forced into an unwanted and horrific relationship.

The movie is long, and could be about 43 minutes shorter had the writers not shoehorned into the story current ‘woke’ virtue signalling. The subplot of a female 007 can be completely removed from the narrative without impinging on the central themes or general plot. Likewise, suggesting that Q is not straight is equally irrelevant, yet clearly intended to help run interference for a franchise long criticized as disrespectful towards women and minorities. Even without the addition of the female 007, these last five films have gone a long way toward changing how women are depicted in Bond films. It is true there have been some glaring throwbacks to the past, like Severine, the doomed ‘girlfriend’ of Silva in 2012’s Skyfall. But for every Severine there are twice as many positive side characters: Eve Moneypenny and M or central characters like Vesper Lynd and Dr. Madeleine Swann.

The addition of Nomi as a replacement 007 in the first act of No Time to Die is used as a way to point out first, that the world has changed and second, the world will continue without James Bond. Both these points can be made more economically. They also lose their impact because the initial friction and insecurities undergirding Nomi’s relationship with Bond give way to mutual respect and her request that he be reinstated as 007. Not only is this B-plot expendable, it is muddled and filled with mixed messages that will not please viewers on either side of the woke divide. Trimming at least thirty minutes of this sub-plot from the film would instantly improve the overall pacing.

While Bond is fighting himself and his instincts as he struggles to hunt down and stop Safin, the underlying threat Bond wrestles with is not a person but an idea. The true villain of No Time to Die is eugenics. The DNA-based viral nanotechnology can be uniquely targeted to wipe out entire ethnicities, or specific families and all relatives, or a single individual. Within the film the weapon is called project Heracles. Heracles (better known in English as “Hercules”) is of course the son of Zeus in Greek mythology—a capricious and selfish pagan god. The weapons project was first developed by SPECTRE for the evil purposes of revenge and extortion with the help of a Russian virologist. It was then confiscated and further developed by MI6 for what M believed would be altruistic and just reasons, only to be stolen by Safin and used for revenge and global chaos. In his efforts to stop the spread of project Heracles, Bond, who in the line of duty has cut short the lives of many, ultimately works to save billions of lives. No Time to Die is focused on the value of life and the need to protect it whether or not it is personally dear to those tasked with defending it.

Bond also has a more personal reason to stop Safin. In a classic Bond showdown, Safin says to Bond, “We have visionary plans for the same goal; only your skills die with your body. Mine will survive long after I’m gone…and life is all about leaving something behind, isn’t it?” Viewers who have seen the film will know what this is alluding to and the bitter irony of Safin’s statement. Bond often finds himself in situations where he must risk his life for others even sometimes for the good of the whole world. No Time to Die is no different except the stakes are much higher.

A key to unlocking No Time to Die is found in the 1969 Bond film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service starring George Lazenby as James Bond and Dame Diana Rigg as his tragic bride Contessa Teresa di Vicenzo. It is the only other Bond film that deals with the questions of Bond’s happiness in the face of true heartbreak. Both the 1969 film and this new film include the Louis Armstrong song “We Have All the Time in the World.” The inclusion of this song is more than an Easter egg; it honours the past as it wraps up the present. It also provides a poignant conclusion where Bond loses everything while gaining everything. In the end Bond’s repentance is genuine and his reconciliation with all that haunts him is complete. His personal sacrifice is lasting and provides viewers a bittersweet yet emotionally satisfying conclusion.

Where does Bond go from here? If viewers stay all the way through the credits they’ll be comforted by the message: “James Bond Will Return.” What that return looks like and who might play the part is completely up in the air. In an interview with Variety, producers Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli noted that audiences “think of [Bond] as being from Britain or the Commonwealth, but Britain is a very diverse place … He can be of any color, but he is male.” While agent 007 may occasionally be female, the character of James Bond will always be James Bond. In other words, “007” is a vocational designation, and James Bond is the man in the calling. The Daniel Craig films make that distinction abundantly clear.

Martin Campbell’s Casino Royale and Sam Mendes’ Skyfall remain the best of modern Bond, but Cary Joji Fukunaga’s No Time to Die sticks the landing. With more focus, it might have been one of the best. It delivers on much of what Bond fans want to see: exciting action and constant entertainment. And no Bond actor has ever received the kind of grand farewell given to Daniel Craig justly honouring his time as 007.

———————

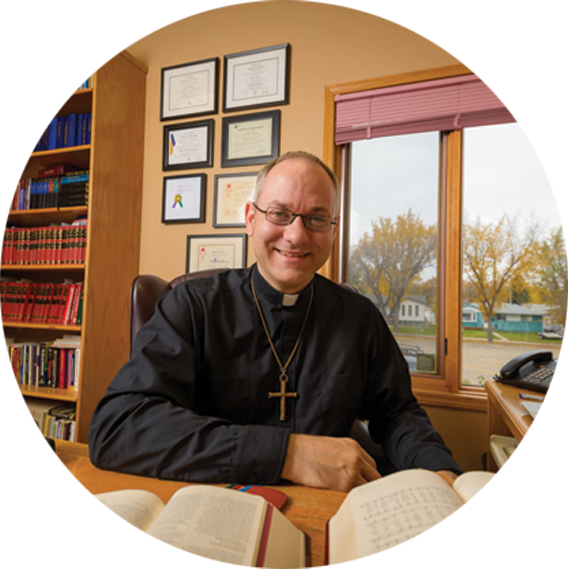

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to The Canadian Lutheran, Reporter; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. For more of his television and movie reviews, check out the Lutheran Movie Review Index.