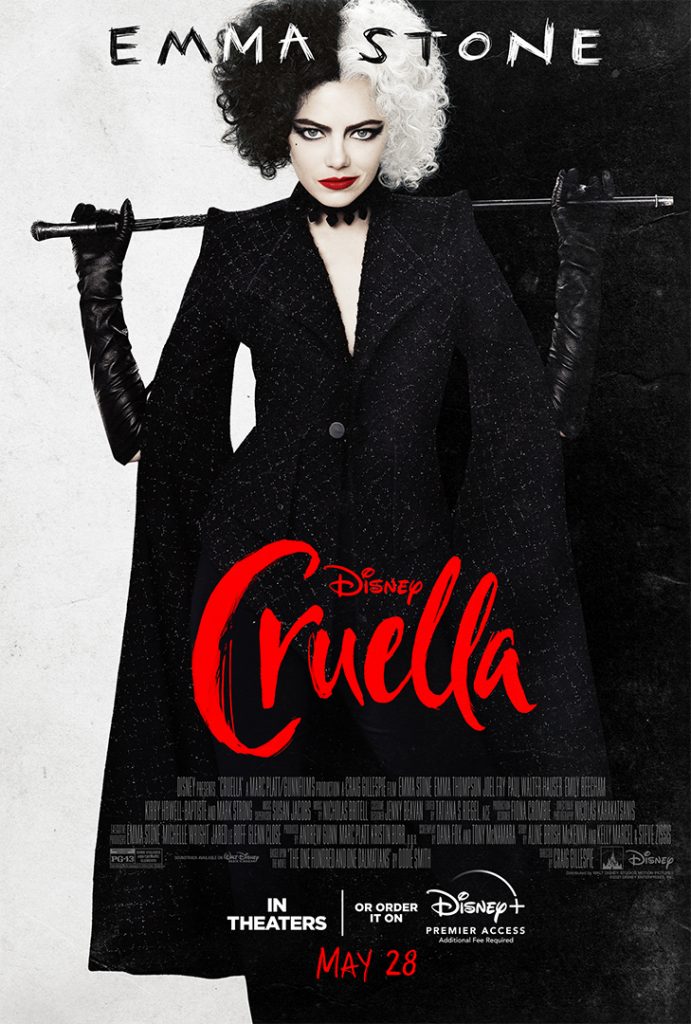

Saint and Sinner in Disney’s Cruella

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

In Disney’s new movie Cruella, Estella/Cruella is an orphan girl with a split personality—one half kind, the other half cruel. While on the run she falls in with a pair of pick-pocketing Dickensian grifters, Jasper and Horace, and eventually pursues her lifelong passion for fashion which leads her into a competition with the Baroness Von Hellman, an established fashion mogul. Her entanglement with the Baroness leads to dramatic personal revelations.

Perhaps the people working in Disney’s live-action film department should be described as “re-imagineers.” With its focus on Cruella de Vil, director Craig Gillespie’s film works to embellish and justify the chain-smoking, devilish fashionista character of the classic 1961 Disney cartoon One Hundred and One Dalmatians. In Cruella, the audience sees a three ingredient recipe of one-part sympathy for the Devil origin story, one-part derivative Joker (2019) meets The Devil Wears Prada (2006) Canal Street knock-off, and one-part character assassination/revision. Gillespie and his writers Dana Fox and Tony McNamara have taken one of Disney’s least likeable villains and made her 95% likeable. Cruella is a clever well-made film which accomplishes what it sets out to do. But is what it sets out to do a good thing?

In 1996 Stephen Herek made a live-action version of the 1961 Disney cartoon 101 Dalmatians starring Glenn Close as Cruella de Vil. She even reprised her role in 2000’s 102 Dalmatians. In these films Cruella was still a villain through and through bent on making fur coats out of Dalmatians. Contrary to the earlier consistent portrayals of the character, in Gillespie’s film Estella/Cruella is an animal lover at heart and would never hurt a dog. She even has her own little dog, Buddy the Terrier, as do her partners in crime. Yes, there are Dalmatians, but they aren’t the lovable Dalmatians of yesteryear. Here they are owned by the Baroness and, as a trio of snarling guard dogs, played a part in Estella becoming an orphan. But don’t worry, the Dalmatians of Cruella get their happy ending too. These details all play into the conceit of the film: Estella/Cruella is misunderstood. If in the original Dodie Smith 1956 children’s novel, Disney cartoons, and subsequent live-action Disney films Cruella was twisted, evil, and only loved dogs for the coats she could make out of them, in this film she must instead love dogs and have ‘justifiable’ reasons for everything she seeks to accomplish.

Sabrina Maddeaux, in her National Post review “Disney killed Cruella de Vil with political correctness,” does an excellent job of detailing the extent to which Gillespie course-corrects this character. The ploy is to give her a good, kind, nice, and likeable side in Estella and shuffle the mischievous, cunning, and disagreeable side into Cruella. In the end, though she embraces Cruella, allowing Estella to “die,” perhaps some part of Estella remains. The movie begins with a voice-over narration by Emma Stone in character which is revealed to be part of a eulogy over the faux funeral of Estella by her “good” friend Cruella. By the end of the film it is clear that the whole story is the story of Estella’s demise as told by Cruella. There is no body in the casket yet it is clear that Cruella doesn’t expect Estella to make future appearances in her life.

Gillespie and his writers Dana Fox and Tony McNamara have taken one of Disney’s least likeable villains and made her 95% likeable. Cruella is a clever well-made film which accomplishes what it sets out to do. But is what it sets out to do a good thing?

There is a Latin theological term used for the tension between the good and the evil in a person: “simul iustus et peccator.” It means “simultaneously justified and sinner” or, in other words, to be at the same time saint and sinner. For Christians, the imputed righteousness of Christ (the “new Adam”) given by God to an individual makes them a saint in the eyes of God. At the same time, there is an inherent wickedness passed down to all people because of the Old Adam’s fall into sin—a narcissistic evil which is turned in on itself and away from God. This leads to tension in the Christian’s life, as St. Paul explains: “I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing” (Romans 7:19).

Christian viewers aware of this theological concept will see themes of the simul iustus et peccator in spades in this movie. Estella/Cruella becomes a kind of personification of this struggle and as Gillespie’s Cruella unfolds, her dominant character traits shift from the more saintly qualities held dear by Estella to the more sinful qualities increasingly seen in Cruella. Viewers of all sorts (Christian or otherwise) will of course desire the good side of the protagonist to win in the end and Gillespie knows this. And yet, as Cruella is in part an origin story, anyone familiar with the earlier movies knows that the good-natured Estella doesn’t win. Therefore the whole character has to be as likeable as possible so the audience will buy into her story and root for her until the end.

To accomplish this, Disney believes Estella/Cruella needs to be ‘woke’ in her views of culture and still be just unhinged enough to remain somewhat recognizable as the original character. What Gillespie uses to justify her actions is her poverty and hardships: being orphaned at a young age and put upon for having bad ‘breeding.’ By the end, however, she has overcome these challenges, capitalized on all of the bad cards she was dealt in life, and climbed the ladder of success to its peak, with all the theft, vandalism, dog-napping, and deception ‘forgiven’ because of her initial class struggles and hard life experiences. But the punk rock aesthetic is fabric deep; the character of Estella and especially Cruella, for all of Gillespie’s posturing, isn’t anti-establishment so much as she is increasingly disagreeable and self interested.

In Cruella, the audience sees a three ingredient recipe of one-part sympathy for the Devil origin story, one-part derivative Joker (2019) meets The Devil Wears Prada (2006) Canal Street knock-off, and one-part character assassination/revision.

A number of Disney characters have received the anti-hero makeover. Recently, Hayabusa the falcon from the 1998’s animated Mulan became the shape-shifting sorceress falcon Xianniang in 2020’s live action adaptation. Here she was no longer a simple villainous sidekick of the invading Mongolian Hun Shan-Yu but instead a misunderstood woman held against her will and forced to do her master’s bidding. Most notable is the reinterpretation of the devilish horned witch Maleficent in 1959’s Sleeping Beauty as Angelina Jolie’s maligned and marginalised Maleficent in the 2014 film Maleficent and its 2019 sequel.

The film’s attempt to rehabilitate the character of Cruella, rooted in critical theory, ideas of social justice, and ideological discussions of class, is not ultimately satisfying—at least not by Christian standards.

Why monkey around with these characters? The answer is likely less motivated by creative concerns and more by economics. The decision to reimagine these back-catalogue villains makes good business sense. Refashioning these characters into Disney ‘princesses’ of a sort, who became victims of circumstance spiralling into villainy gives a new angle on the characters and opens up new merchandizing opportunities. Even the choice to have Cruella set aside her signature opera length cigarette holder is rooted in an economic concern. Disney has explicitly made it a policy to avoid depictions of smoking, as there is increasing pressure (including from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control) to have movies with smoking given higher-age ratings. The Disney policy has limited exceptions, including scenes that “portray cigarette smoking in an unfavourable light or emphasize the negative consequences of smoking.” But in the case of Cruella, they are trying hard not to portray her in an unfavorable light. And so the cigarettes need to go away. The same could be said for Gillespie’s lack of fur coat fashions for Cruella in his film.

Disney’s savvy marketing machine can also be seen in the musical score for Cruella. Much like 2014’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Cruella is punctuated with music familiar to Baby Boomer grandparents and Gen X parents of the children at whom the film is aimed. The result is “fun for the whole family,” nostalgic, and comforting in that pop-culture reference sort of way. All of this is intended to hook older viewers and soften their opinion of the film’s story. Careful viewers will also notice two uses of music intended to bolster the film’s sympathy-for-the-devil angle: first, the 1968 Rolling Stones song “Sympathy for the Devil” is used in the film’s final moments along with the less obvious use of Jimmy Durante’s 1965 recording of the song “Smile”—a song which was recently used to great effect in 2019’s Joker. In both the R-rated Joker and the PG/PG-13-rated Cruella, the melancholic yet hopeful and encouraging “Smile” is juxtaposed against the central character’s decent into infamy.

Christian parents should watch Cruella before deciding whether to allow their kids to see it. The film has no nudity, sex, brutal violence, or crude language but it does have a rather dark aesthetic weaving in proto-Goth and Punk fashion, along with a Ziggy Stardust-esque vintage clothing shop owner and tailor written into the movie to appeal to LGBTQ+ viewer. Since the plot revolves around the fashion industry, these last points are hardly unexpected but do check certain boxes for Disney. The primary concern for families though is the glamorization of evil and the continual justification of evil actions by a character the script works hard to make likeable. If you and your family choose to watch this film, it might be a good plan to review the Ten Commandments in the Small Catechism before and after viewing to provide an opportunity for a family discussion about the central character and the general plot.

Overall, the film downplays the dangers of evil actions which may be harder to see during a casual viewing experience because Emma Stone, Emma Thompson, Joel Fry, and Paul Walter Hauser are such excellent actors. So too the genuine humour and high quality production contribute to the likability of the film. But just as beauty doesn’t equal goodness, neither do fun and likability necessarily equal goodness. The film’s attempt to rehabilitate the character of Cruella, rooted in critical theory, ideas of social justice, and ideological discussions of class, is not ultimately satisfying—at least not by Christian standards. For the Christian, evil needs to be sublimated and subdued, not embraced, excused, or presented as justifiable. Regardless of how cleverly-made, entertaining, and likable the film is, all viewers would do well to consider how Disney’s re-imagining of Cruella interacts and contrasts with their own views on life and morality.

———————

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to The Canadian Lutheran, Reporter; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. For more of his TV and Movie Reviews, check out the Lutheran Movie Review Index.