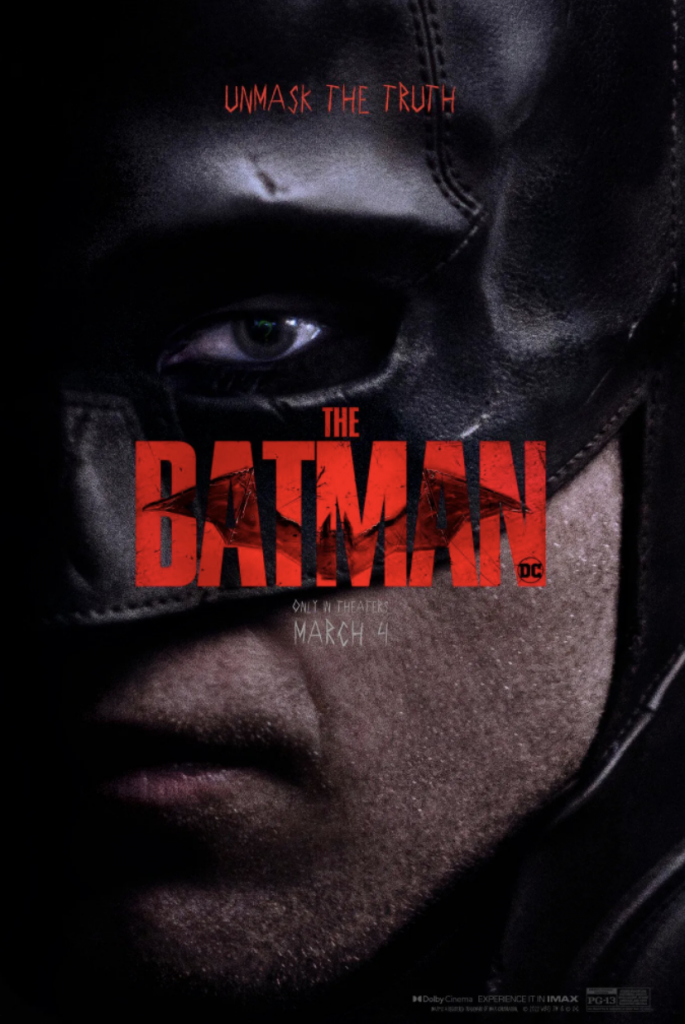

The Batman: A darker caped crusader

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

When Mayor Don Mitchell, Jr. is murdered, Lt. James Gordon brings Gotham City’s cowled vigilante into the homicide investigation, because a card addressed to “The Batman” is found at the crime scene. The card contains a cipher and a riddle which leads to the unravelling of high-level corruption in the mayor’s office, the city police, the court system, and Gotham’s elite class. More bodies crop up murdered in grizzly horrific ways, each pointing to some kind of retribution for corruption, and each accompanied by riddles and ciphers addressed to the Batman. This detective serial-killer mystery is the backdrop for a darker grittier dive into the character of Bruce Wayne/Batman.

Director Matt Reeves provides a well-crafted film with The Batman—but potential viewers will want to remember that just because a film is well-crafted it still might not be to their liking. Audiences burnt out on dark violent films will want to steer clear of this version of Batman. On the other hand, there are some smart choices made that tidy up some of the sillier elements of the Batman franchise. For all its brooding intensity, Reeves delivers a film with the look and feel of an R-rated film without the R-rated violence, nudity, and sex—but parents and the tender-hearted will want to keep in mind that the film’s rating tells only half the story. If Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy seemed too dark and intense, or Tim Burton’s 1989 and 1992 films, then you will find The Batman also too intense—and then some. This is nothing like the 1960s KAPOW! ZAP! BAM! television series or even the 1990s Batman: The Animated Series.

Mob bosses like Carmine Falcone and his underling club owner Oz/The Penguin have the look and feel of characters ripped from your average gangster movie, minus the Italian-American trappings. And the Riddler—the central antagonist in The Batman—is something straight out of the serial killer genre that have littered screens for decades. Unlike Jim Carrey’s over-the-top screwball performance in 1995’s campy Batman Forever, Paul Dano plays the Riddler as an unhinged Unabomber/Zodiac-type killer, seeking justice against a system replete with what he sees as false promises of renewal. His enemies are liars and weak officials, like District Attorney Gil Colson, who quickly fall in bed with organized crime and allow corruption. Reeves’ Batman has stumbled into something the 16th century theologian Martin Luther would describe as God punishing one criminal by means of another. The question is whether the philanthropist Wayne’s family is party to Gotham City’s historic crimes. Lurking in the shadows is another question: are Batman and the Riddler so different? Batman calls himself “vengeance” and the Riddler seeks the same. Reeves makes both men orphans who use methods outside the law to bring retribution on criminals, positioning them as two sides of the same coin minted in a corrupt system.

If a dark and gritty film noir version of Batman is not your style, perhaps it’s a good time to revisit some earlier, more lighthearted Batman television and films.

This is a familiar theme in the Batman franchise but Reeves pushes it further by explicitly bringing in the Old Testament concept of “the sins of the father.” But there are key differences between the idea in The Batman and in Scripture: the Bible makes it clear that God is the one who punishes the children of the father for the father’s sins. In the Ten Commandments, God warns idolaters who worship false gods that He visits the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate Him (Exodus 20:5). This ominous promise is reiterated at the end of the giving of the Law when God proclaims He is “the LORD, the LORD, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, but who will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation” (Exodus 34:6–7).

It’s important to remember, however, that this vengeance is left in God’s hands, not in the hands of men. In fact, God expressly limits the extent to which the legislative law of the people may pursue vengeance: “Fathers shall not be put to death because of their children, nor shall children be put to death because of their fathers. Each one shall be put to death for his own sin” (Deuteronomy 24:16). And in the Levitical Law of the Old Testament, the LORD teaches, “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against the sons of your own people, but you shall love your neighbour as yourself: I am the LORD” (Leviticus 19:18).

Within Christianity it is important to remember that while God allows suffering He doesn’t actively will it; His nature is gracious and merciful as well as righteous and holy. Yet even though His patience is long-suffering, His love for the oppressed and downtrodden—those abused by criminals and people misusing the authority He gives them—will cause Him to act on their behalf. In The Batman, both Batman and the Riddler must face the fact that they have, from the shadows, assumed roles best reserved to God, acting as judge, jury, and executioner—but unlike God, they don’t likewise possess the traits of mercy, love, and forgiveness.

St. Paul in his letter to the Romans provides a different approach for people tempted to take vengeance into their own hands: “Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.’ To the contrary, ‘if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals on his head.’ Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good” (Romans 12:19–21). By the end of The Batman, Bruce Wayne is beginning to learn this lesson, saying: “Vengeance won’t change the past. Mine or anyone else’s. People need hope.” He understands that people need more from him than just vengeance.

The Christian view would be that the world still needs vengeance, just not vengeance in the hands of the wrong people, or people for whom such authority has not been given. Even those who have received such authority need to both fight the temptation to misuse it and constantly turn the vengeance back into God’s hands. Anyone interested in what that looks like would be well served by reading the Biblical account of the life of King David, especially in light of the Psalms that he wrote (see, for example, Psalm 10:15, where the king returns vengeance back to God).

Of course, the decision to transition Batman more into a symbol of hope than a crime fighter whom criminals fear brings its own problems. If the idea is to make Batman more like Superman, then Reeves doesn’t get who Batman is supposed to be. Having Batman, for the purposes of dramatic tension, struggle with vengeance and hope may be a fruitful direction for the character when a second Reeves film is developed. Here’s hoping they lean into that struggle and don’t just turn Batman into a woke parody of himself, or attempt to make him into something he was never intended to be. Reeves’ promised “embodiment of hope” approach if pressed too far will be as much trouble to maintain as the idea of Batman simply being an embodiment of vengeance.

The line between where Bruce Wayne ends and Batman begins in Reeves’ film is blurry. He is mostly the same whether wearing the bat suit or not, and seems to internalizes the pain and suffering of the people of Gotham. Where Reeves plans to take the character remains to be seen, but Robert Pattinson’s version is certainly compelling, albeit mopey and downbeat by comparison with some other depictions of Batman. This Bruce Wayne/Batman is more in keeping with the judges of the Old Testament: noble, violent, desirous of justice for an oppressed people, yet personally flawed. While he is a man of constant sorrow, this Batman is no Christ figure.

From a theological perspective, Jesus ultimately resolved the problem of the sins of the fathers and the sins of all people by taking those sins on Himself. He became sin who knew no sin of His own (2 Corinthians 5:21), accepting the wages of those sins, which is death, so that His righteousness could be applied to the sinner by grace. The Riddler wants someone to pay for the lies, pain, and suffering of Gotham, and he thinks he knows who that should be—and it’s not Jesus. The Riddler tries to play God and fails because he doesn’t understand mercy; Batman discovers he needs mercy because he can’t singlehandedly save Gotham.

If relating these characters and their motivations to the biblical themes of sin and vengeance seems a stretch, consider how Reeves repeatedly uses a the familiar Roman Catholic song, Ave Maria. This prayer, spoken to the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus, is a plea for mercy by sinners, asking for rescue from their sins in the hour of death. The choice to repeatedly use this music and its emphasis on seeking mercy in the face of death invites religious reflection on the film.

Woven throughout the film is the relationship between Batman and Selina Kyle/Catwoman. Through the course of his investigations, Batman meets Kyle as she is the friend of one of the murder victims. This film provides a grounded and believable reason for Batman and Catwoman’s relationship, and while there is some flirting and a couple kisses, their relationship is not hyper-sexualized. Sometimes Catwoman goads Batman, sometimes Batman protects her from doing the wrong thing, yet there is a fair amount of give and take between the two. Selina Kyle spouts some woke bits of dialogue but for the most part Batman doesn’t engage her idealism, turning down her anti-capitalist invitation to run away together and rob the rich and powerful. Of the film’s African American characters, hers is the most developed and realized. Other characters like Lt. James Gordon and mayoral candidate Bella Reál are essentially virtue-signalling placeholders without much development or back story; they simply act as a foil to the corrupt powerful rich white men targeted by the Riddler. Another underutilized character is Wayne/Batman’s butler Alfred. In this film he is reduced to a plot device and general reminder of Bruce Wayne’s past. Hopefully Reeves will do more with the character moving forward.

The Batman may not be the Batman everyone wants right now. If a dark and gritty film noir version of Batman is not your style, perhaps it’s a good time to revisit some earlier, more lighthearted Batman television and films. That’s especially good advice for younger viewers. Remember, being a fan doesn’t mean you’re required to watch every film or television show in a franchise. Nostalgia alone should not drive viewers to the theatres; film makers still need to produce worthwhile projects without banking on built-in fan audiences.

———————

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to The Canadian Lutheran, Reporter; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. For more of his television and movie reviews, check out the Lutheran Movie Review Index.