With Angels and Archangels and All the Company of Heaven: The Treasure of the Liturgy

by Thomas Winger

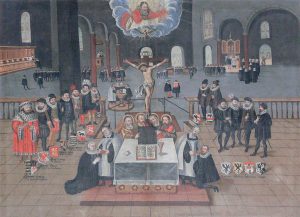

A painting of the Lutheran Divine Service in St. Nicholas Church (Luckau, Germany).

Fifty years ago a Lutheran pastor dryly observed that everyone’s using the word “liturgy,” but that it means something different to each person. To some it just means “an order of service.” To others it means “a type of church service which they call formal and regard as cold and unspiritual.”

We could dig into the history of the Greek word “liturgy,” but perhaps it’s enough to say that it really means neither of the above! At its heart, the liturgy is a “divine service,” as our hymnals say. It’s God at work through His Word and sacraments to deliver the gifts of forgiveness, life, and salvation. And it’s our divinely-inspired response to those gifts in prayer, praise, and thanksgiving. But how exactly does that happen?

Sometimes we talk about the liturgy as if it’s just a manmade order—written by committee or inherited from our forefathers. Now it’s true that many of the details are worked out in hymnal committees and aren’t given to us by God; but those bits aren’t really the liturgy either. If they were, then Jesus’ harsh words to the Pharisees, who criticised His disciples for eating without ritual hand-washing, would apply to us: “In vain do they worship Me, teaching as doctrines the commandments of men” (Matthew 15:9). So where does the liturgy come from?

It’s really both biblical and catholic.

The Liturgy and the Bible

Firstly, in its essence it comes from Jesus Himself. The liturgy is a continuation of Jesus’ earthly ministry. Jesus taught that He was the fulfilment of the Old Testament Temple and its worship (John 1:14; 2:21). He was the presence of God on earth, teaching His people (Luke 10:38-42), forgiving sinners and eating with them (Mark 2:15-17).

Secondly, Jesus commanded and gave authority to His apostles to continue doing what He had done. He told them to make disciples by baptising and teaching (Matthew 28:19-20), to preach repentance for the forgiveness of sins (Luke 24:47), to absolve sinners (John 20:23), and to give out His life-giving Body and Blood (1 Corinthians 11:23-26). And He promises that where we do these things, He is with us (Matthew 18:20; 28:20). So the liturgy is really Jesus at work, for when we gather in His name, He continues to carry out His ministry of teaching, forgiving, and feeding us. And He is the one who carries our prayers and praise back to His Father’s throne (Hebrews 7:25; 13:15).

Thirdly, we read throughout the rest of the New Testament how the early apostolic church carried out what Jesus had given them to do. After the great crowd at the Temple on Pentecost were baptised, “they were devoting themselves to the teaching of the apostles and to the communion in the breaking of bread and to the prayers” (Acts 2:42). That’s the liturgy: they gathered for Word and Sacrament with prayer. Paul tells Timothy to devote himself “to the public reading of Scripture, to preaching, to teaching” (1 Timothy 4:13), and that he should pray for kings and the world’s salvation (1 Timothy 2:1-4). Acts tells us that the early church gathered each Sunday for the “breaking of the bread” (the Lord’s Supper) in remembrance of Jesus’ resurrection. So when we gather to do the same, we’re also being faithful to Jesus and worshipping in the way He gave us in the Bible.

The liturgy is God at work through His Word and sacraments to deliver the gifts of forgiveness, life, and salvation. And its our divinely-inspired response to those gifts.

But the liturgy is biblical in another way, too. The Lutheran Service Book (LSB) has done us a great favour by including Bible references next to the words of the divine service. This reminds us that we’re not only doing what Jesus told us to do, but that we’re doing it using God’s very Word. Like a proud Father, God is most pleased with us when we speak back to Him the words He first taught us. A teacher of mine liked to say that the liturgy is 99.44% Scripture. When we use His words, we don’t have to worry that our worship might not be pleasing to Him and fall under the condemnation of the Pharisees. That’s why we use God’s own words to respond to Him with joyful praise and thanksgiving for His mercy to us in Jesus Christ.

The Liturgy as our Catholic Heritage

Now, we also use the word “liturgy” in another sense: to refer to the particular way this scriptural content has come together over many centuries of church history. Martin Luther wrote in 1520: “The [divine] service now in common use everywhere goes back to genuine Christian beginnings.” Our Lutheran liturgy is part of the “Western rite” (shared with Anglicans and Roman Catholics); and it has much in common also with the “Eastern rite” (used by Orthodox churches). This long history and broad Christian usage gives the liturgy stability and strength. It protects us from the whims of individuals. It strengthens the unity of the church by giving us common words and ways of worship, focused not on ourselves but on Christ’s gifts. The liturgy is therefore both “ecumenical” and “catholic” in the best sense of those words: it belongs to the whole Christian church.

There have been times, of course, when the church got it wrong. The Lutheran Reformation was very much concerned with worship. The medieval church had turned the Lord’s Supper into a sacrifice offered up to God—and it affected the words of the liturgy. But rather than throwing out the whole thing, Luther and his colleagues performed careful surgery to cut out what was bad and keep what came from Scripture and served the Gospel. Introducing his reform of the Latin mass in 1523, Luther wrote: “It is not now nor ever has been our intention to abolish the liturgical service of God completely, but rather to purify the one that is now in use from the wretched accretions which corrupt it and to point out an evangelical use.”

This is what we gladly receive in our Lutheran hymnals: the Gospel-centred, biblical liturgy of the Church. LSB offers five musical settings of the divine service, but their content is pretty much the same. The headings in the services tell us that we’re getting “The Service of the Word” and “The Service of the Sacrament,” as Jesus gave us to do (with a preparation rite beforehand). The “Propers”—the Introit, Scripture readings, and so forth, which change each week—offer us “the full counsel of God,” presenting His biblical Word without favouritism. The major texts of the liturgy—what we call “Ordinary” because they don’t normally change—join us “with angels and archangels and with all the company of heaven” (the Preface) by singing the songs of Scripture. In this way we get variety and stability in balance.

Next time you sing the songs of the historic liturgy, think about where they come from and where they take us. The Kyrie gives us the words of blind Bartimaeus, “Lord, have mercy!”—reminding us that we come before God with nothing to offer, just seeking His help. The Gloria in Excelsis sings the Christmas hymn of the angels, because Christ is coming in the flesh to us as well. The Creed sums up the whole of Scripture to teach us our Triune God’s way of salvation. The Sanctus borrows another angelic song, heard by both Isaiah and John in their visions of heaven, to open our eyes to see how the divine service brings us before the very throne of God. And as we then sing “Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord,” our eyes are turned to the altar where He comes to feed us on earth. The Agnus Dei gives us divine words to ask that Lamb of God for the gift only He can give: to take away our sins and grant us peace. And as we depart from that altar, we sing in the Nunc dimittis with ancient Simeon that we are now prepared to depart this world, having seen God’s salvation. What a treasure!

Rev. Dr. Thomas Winger is President of Concordia Lutheran Theological Seminary in St. Catharines, Ontario. He is also the author of Lutheranism 101: Worship, available from Concordia Publishing House.